Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona

Descobreix el Modernisme a Barcelona

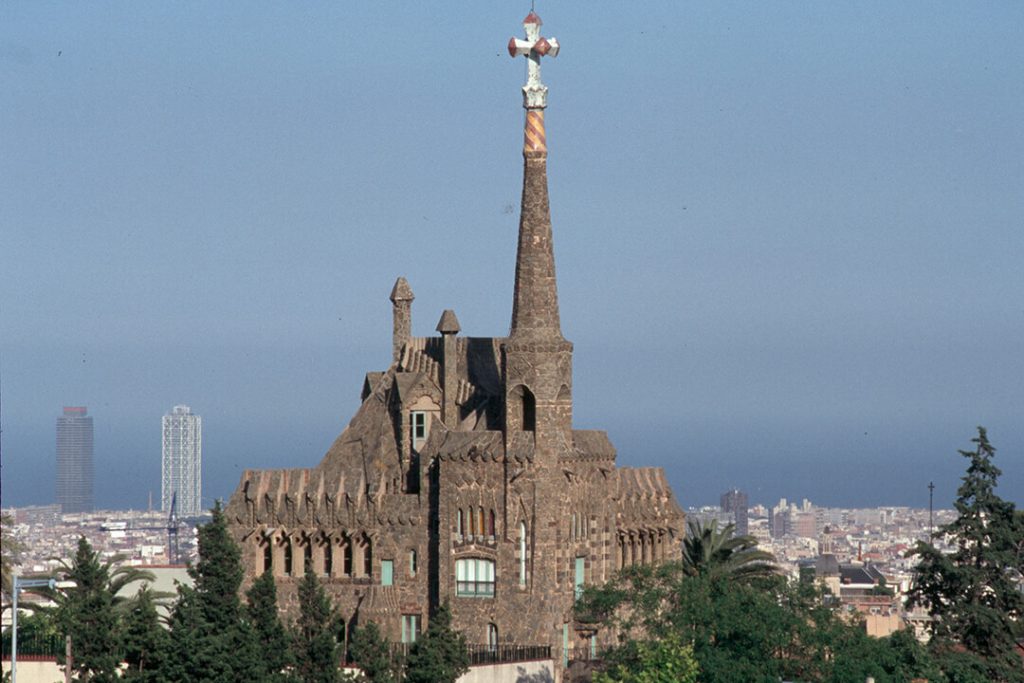

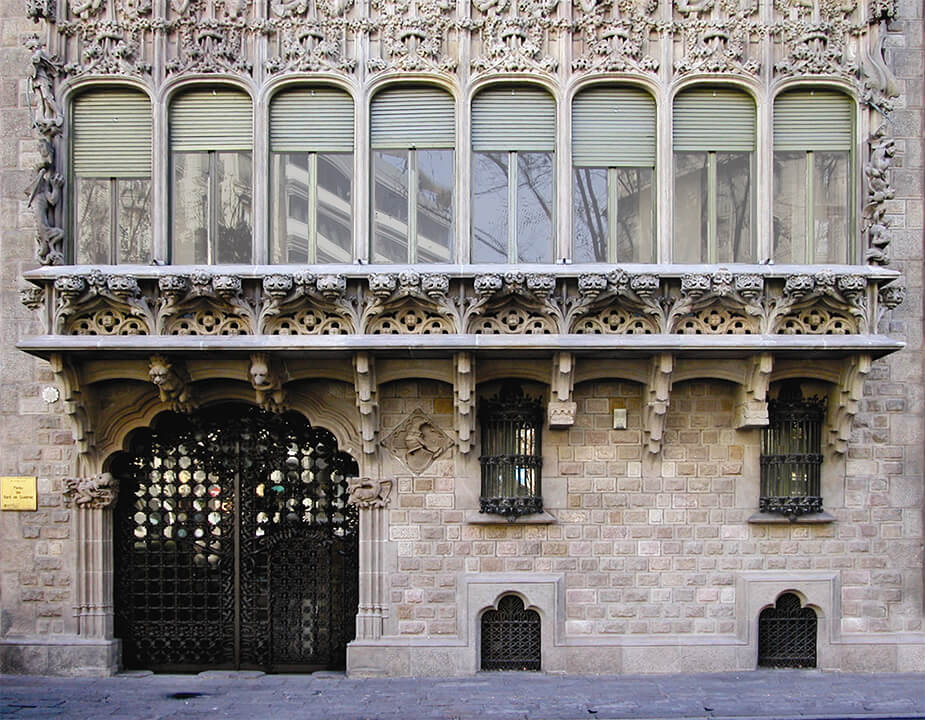

La Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona és un itinerari per la Barcelona de Gaudí, Domènech i Montaner i Puig i Cadafalch, que juntament amb altres arquitectes van fer de Barcelona la gran capital del Modernisme. Amb aquesta ruta podreu conèixer a fons impressionants palaus, cases sorprenents, el temple símbol de la ciutat i un immens hospital, i també obres més populars i quotidianes com ara farmàcies, bars, botigues, fanals o bancs. Obres modernistes que demostren que el Modernisme va arrelar amb força a Barcelona i que encara avui és un art viu i viscut.

Notícies

Li oferim les últimes notícies en relació amb la Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona. Gaudiu de les obres de la ruta des d’una altra perspectiva.

La Casa Batlló (1904-1906), obra d’Antoni Gaudí, ha iniciat la primera restauració integral de la façana posterior de l’edifici i el seu pati, el jardí privat de la família Batlló. Gaudí va concebre la façana posterior com un jardí vertical que simbolitza una planta enfiladissa florejada que puja pels laterals i es troba a la […]

Més informació

Els historiadors de l’art Marta Saliné, també especialista en mosaics, i Jordi March, van descobrir l’any passat que el pintor Joaquim Mir era l’autor d’un mosaic situat a l’entrada de la Casa Navàs de Reus. El descobriment el van fer durant la preparació d’una conferència pel IV Congrés Internacional CoupDeFouet, dedicat a l’obra de Lluís […]

Més informació

La Generalitat de Catalunya ha declarat la Casa Sayrach com a Bé Cultural d’Interès Nacional, en la categoria de Monument Històric. La Casa Sayrach (Diagonal, 423-425) és una obra modernista projectada l’any 1915 per l’arquitecte Manuel Sayrach i Carreras, i és un dels exemples singulars del Modernisme barceloní, amb les seves formes corbes de la […]

Més informació

Els propers 24, 25 i 26 de maig de 2024 se celebrarà una nova edició de la Fira Modernista de Barcelona, que aquest any estarà dedicada al dramaturg i poeta Àngel Guimerà (1845-1924) en commemoració del centenari de la seva mort. La Fira es farà el mateix lloc de l’any passat, al carrer Bruc, entre […]

Més informació

Ahir 10 de març de 2024 va morir Ferran Ferrer Viana, director de Desenvolupament Estratègic Corporatiu (1981-2001) i gerent de l’Institut del Paisatge Urbà i Qualitat de Vida, de l’Ajuntament de Barcelona, des d’on va crear l’any 1997 la Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona, inaugurada el 18 d’abril per l’alcalde Pasqual Maragall. Sota la gerència […]

Més informació

Les principals obres

Xarxes Socials

Obtingueu la Guia de la Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona.

La Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona és un itinerari que recorre la Barcelona de Gaudí, Domènech i Montaner i Puig i Cadafalch, que, juntament amb altres arquitectes, van fer de Barcelona la gran capital de l'Art Nouveau Català. Amb aquesta ruta podeu descobrir impressionants palauets, cases sorprenents, el temple que és el símbol de la ciutat i un immens hospital, així com altres treballs més populars i quotidians, com farmàcies, botigues, llanternes o bancs. Obres del Modernisme que demostren que l'Art Nouveau es va enraonar a Barcelona i que fins i tot avui dia encara és un art viu, un art viscut.

La Guia de la Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona es pot adquirir als nostres centres de Modernisme.