Ruta del Modernisme de Barcelona

Home /

The 1 day route

If you have only one day, this guide offers the One-day route, which bypasses all the detours. It can be completed comfortably on foot in one day, and still leaves time for one full visit inside a building. We recommend that you do the whole walk first and then return to the building of your choice to go inside, particularly in winter to make full use of daylight. The One-day route is marked on the maps with a green line, which represents the backbone of Barcelonan Modernisme: la Rambla, Passeig de Gràcia, Avinguda Diagonal, and Avinguda Gaudí.

Arc de Triomf i Casa Estapé – Park Güell

A good place to start the Barcelona Modernisme Route is the ARC DE TRIOMF (TRIUMPHAL ARCH. Passeig de Lluís Companys, s/n), built in 1888 at the top of Passeig de Lluís Companys to a design by Josep Vilaseca, which presided over the entrance to the 1888 Exhibition.

The one-day Route starts here. Although this walking tour does not visit all of the most recommended Modenista monuments, it gives a wide, in-depth view of this architecture and is a good option to discover the city in general. This guide will lead you around if you follow the icons .on the text margin and the green line on the map.

Before continuing the route down to the Parc de la Ciutadella, you can make a slight detour up Passeig de Sant Joan to ![]() CASA ESTAPÉ (1) (ESTAPÉ HOUSE. Passeig de Sant Joan, 6) by Bernardí Martorell i Rius (1907), which is easily recognised by its curious dome by Jaume Bernades. Nearby the Arch, on the short Avinguda de Vilanova, you can see the building of

CASA ESTAPÉ (1) (ESTAPÉ HOUSE. Passeig de Sant Joan, 6) by Bernardí Martorell i Rius (1907), which is easily recognised by its curious dome by Jaume Bernades. Nearby the Arch, on the short Avinguda de Vilanova, you can see the building of ![]() HIDROELÈCTRICA (2) (Avinguda de Vilanova, 12), a Modernista building of the former Central Catalana d’Electricitat built by Pere Falqués i Urpí between 1896 and 1899, which can sometimes be visited during office hours.

HIDROELÈCTRICA (2) (Avinguda de Vilanova, 12), a Modernista building of the former Central Catalana d’Electricitat built by Pere Falqués i Urpí between 1896 and 1899, which can sometimes be visited during office hours.

Continue down Passeig de Lluís Companys to the PARC DE LA CIUTADELLA (CITADEL PARK. Passeig de Pujades, s/n, Passeig de Picasso, s/n). This park can be considered to be the first great architectural expression of the Modernista movement. As its name indicates, the site had formerly been occupied by a military citadel, built in the early 18th century after the defeat of Barcelona in the War of Succession. The city was severely punished when it fell after a long siege, and the Citadel (together with the new walls and Montjuïc castle) was used by the Bourbon dynasty to keep the city under military control for over 150 years. In the mid-19th century, after years of petitioning by the citizens, the government in Madrid agreed to allow the walls and the Citadel to be demolished to make room for the urban development of the city. This made it possible to create the Eixample (“Enlargement”) and the new Citadel Park.

Before the park was built, however, the land was used as the site for the 1888 Universal Exhibition. Though it was definitely less important than other similar exhibitions, such as those of Paris and London, like them it aimed to reveal the marvels of the new technologies of the incipient capitalist industry, and to make Barcelona known worldwide.

The pavilions and the infrastructures were built rapidly and with a great deal of improvisation. Experienced architects such as Josep Fontserè worked alongside young graduates such as Lluís Domènech i Montaner, who demonstrated his impressive talent for management and coordination, especially in the Gran Hotel Internacional (no longer standing), a building with a capacity for 500 guests which Domènech’s team built in less than 60 days. Legend also created many myths and rumours about the role played by Antoni Gaudí in the construction of the Parc de la Ciutadella. Some claim that he collaborated with Josep Fontserè in the building of the waterfall and perhaps also the cistern on Carrer Wellington. Others see Gaudí’s mark on the railings of the main gate of the park, and the disappeared pavilion of the Companyia Transatlàntica.

Though the park itself is not considered to be a Modernista garden, it contains some outstanding works in this style. Just beside one of the side doors of the park, in Passeig de Pujades, is the building that was destined to be the Café-Restaurant of the Universal Exhibition. It was built between 1887 and 1888 by Lluís Domènech i Montaner in exposed brickwork, an unusual technique at the time, and is one of the first examples of Barcelona Modernisme.

Its crenellated wall, its frieze of coats of arms and its sobriety give it a certain medieval appearance, which is highlighted by the eclectic combination of Catalan arches, large Roman windows and Arabic arches. Since 1920 the building, popularly known as the Castell dels Tres Dragons (Castle of the Three Dragons), has housed the ![]() MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA (3) (MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY),which, together with the Geology Museum, forms the Natural Science Museum. The Castell dels tres Dragons houses the zoology collection and permanent exhibition, and the temporary exhibition rooms of the Natural Science Museum, presided over by a magnificent skeleton of a whale. The building was recently restored respecting the architectural values of the construction and furniture. Nearby are two delightful buildings, the

MUSEU DE ZOOLOGIA (3) (MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY),which, together with the Geology Museum, forms the Natural Science Museum. The Castell dels tres Dragons houses the zoology collection and permanent exhibition, and the temporary exhibition rooms of the Natural Science Museum, presided over by a magnificent skeleton of a whale. The building was recently restored respecting the architectural values of the construction and furniture. Nearby are two delightful buildings, the ![]() HIVERNACLE (4) (GREENHOUSE. Passeig de Picasso, s/n. Parc de la Ciutadella), a work by Josep Amargós i Samaranch (1883-1887) that is currently used for all types of social event, and the

HIVERNACLE (4) (GREENHOUSE. Passeig de Picasso, s/n. Parc de la Ciutadella), a work by Josep Amargós i Samaranch (1883-1887) that is currently used for all types of social event, and the ![]() UMBRACLE (5) (SHADE HOUSE. Passeig de Picasso, s/n. Parc de la Ciutadella), built by Josep Fontserè i Mestres in 1883-1884. It is certainly worth sparing a few minutes to have a look inside both of them and walk around the splendid collection of plants they protect.

UMBRACLE (5) (SHADE HOUSE. Passeig de Picasso, s/n. Parc de la Ciutadella), built by Josep Fontserè i Mestres in 1883-1884. It is certainly worth sparing a few minutes to have a look inside both of them and walk around the splendid collection of plants they protect.

From the Parc de la Ciutadella, walk into the old city centre along Carrer Fusina or Carrer de la Ribera, which will take you to the MERCAT DEL BORN (BORN MARKET. Plaça Comercial, 12), until the 1970s the main wholesale market of the city. This structure of iron, wood and glass designed by Josep Fontserè and built in 1876 is an excellent example of the architectural forerunners of Modernisme, which excelled in the design of new structures made possible by using new industrial materials, and in the importance given to natural light. Inside are the ruins discovered in 2001, which are part of the buildings of the old Barcelona that were demolished to make way for the military Citadel in 1715. These ruins are sometimes open to the public and are part of the History Museum of the City of Barcelona (for more information, call 933 190 222).

Right opposite the market, Passeig del Born, perhaps the only street in Barcelona that is still fully paved in cobblestones characteristic of the first half of the twentieth century. All along this part of the walk we will come across some of the oldest streets of Barcelona, some of them opening under vaults in a medieval style, with names that in many cases refer to the old crafts guilds that grouped together in each one. Passeig del Born will lead you to the BASÍLICA DE SANTA MARIA DEL MAR (THE HOLY MARY OF THE SEA’S BASILICA. Plaça de Santa Maria, s/n), dating from the 14th century and one of the most important Catalan Gothic churches. If you go round the building on Carrer Santa Maria you will come to the FOSSAR DE LES MORERES (MULBERRY TREE GRAVEYARD. Plaça del Fossar de les Moreres, s/n), one of the main symbols of Catalan nationalism. According to tradition here lie those who died defending Barcelona in the siege of 1714, which was the final episode in the War of Succession in which the European dynasties of Austria and Bourbon fought over the kingdoms of Spain. The memorial placed here in 2001 commemorates this heroic defence of Barcelona by the Catalan militia, who for over a year resisted the alliance of the Spanish and French armies, far superior in number and technology.

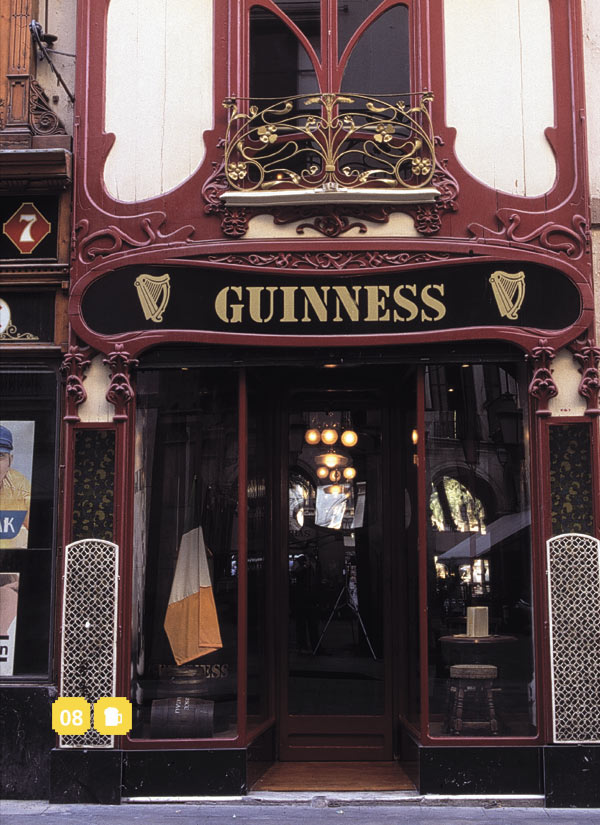

On the other side of the Basilica, continue along Carrer Argenteria, cross Via Laietana and go up Carrer Jaume I, which takes you to the heart of the city, the Plaça de Sant Jaume. This square has been the political and administrative centre of the city since mediaeval times: on the right is the Renaissance façade of the Generalitat de Catalunya, the Catalan autonomous government, while on the left is the Barcelona City Council or Ajuntament, its neoclassical façade hiding a Gothic interior. Just after the square you can turn left into Carrer del Pas de l’Ensenyança to visit the cocktail bar El Paraigua, decorated with original Modernista elements ![]() MOLLY’S FAIR CITY (6)(Ferran, 7-9), which was previously a shop and still has much of the original Modernista decoration on both the outside and the inside (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants). Just opposite this pub is the entrance to Plaça Reial, one of the busiest places in the city, with a considerable range of bars and night clubs. This square was the first important urban renewal project in 19th-century Barcelona, and occupies the site of the former Santa Madrona Capuchin monastery, which was demolished in the mid-19th century. The design of this urban space, with its characteristic porticos, is the work of the architect and urbanist Francesc Daniel Molina, who was inspired by the French urbanism of the Napoleonic period and conceived it as a residential square formed by buildings of two storeys plus an attic, built over archways. Right in the centre of the square is the Three Graces fountain, and on both sides of it the complex

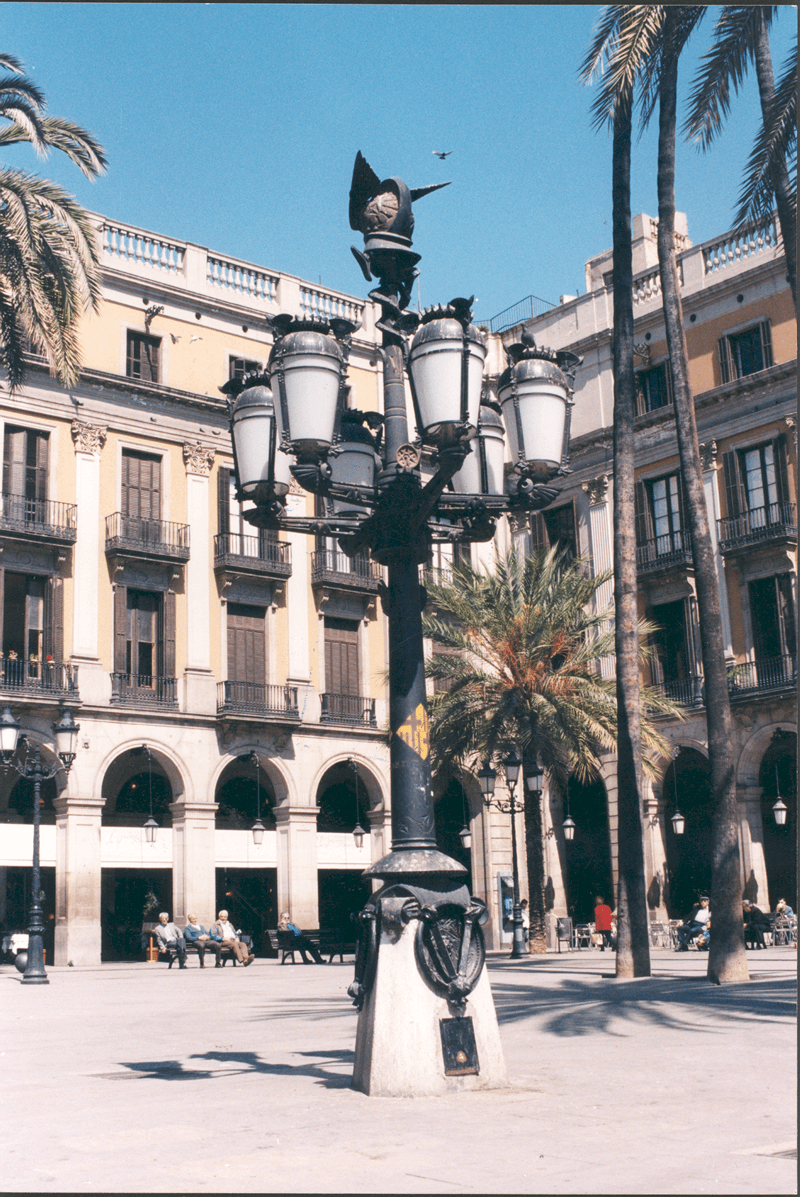

MOLLY’S FAIR CITY (6)(Ferran, 7-9), which was previously a shop and still has much of the original Modernista decoration on both the outside and the inside (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants). Just opposite this pub is the entrance to Plaça Reial, one of the busiest places in the city, with a considerable range of bars and night clubs. This square was the first important urban renewal project in 19th-century Barcelona, and occupies the site of the former Santa Madrona Capuchin monastery, which was demolished in the mid-19th century. The design of this urban space, with its characteristic porticos, is the work of the architect and urbanist Francesc Daniel Molina, who was inspired by the French urbanism of the Napoleonic period and conceived it as a residential square formed by buildings of two storeys plus an attic, built over archways. Right in the centre of the square is the Three Graces fountain, and on both sides of it the complex ![]() FANALS (7) (LAMP-POST. Plaça Reial, s/n) with six lamps designed by a young Antoni Gaudí in 1878.

FANALS (7) (LAMP-POST. Plaça Reial, s/n) with six lamps designed by a young Antoni Gaudí in 1878.

The two lamp-posts are decorated with the attributes of the god Hermes, the patron of shopkeepers: a caduceus (a messenger’s wand with two snakes wound round it) and a winged helmet. Like Plaça Reial, many other places in the historic centre of Barcelona were built on sites formerly occupied by monasteries and churches that were confiscated by the Spanish government and sold to private owners. These measures, which were carried out in 1837 and known as Mendizábal’s disentailment, led to the auction of eighty percent of the land owned by the church within the city walls of Barcelona. The disentailment rapidly led to a thorough and long-lasting transformation of the urban landscape of Barcelona. There are many examples. The Boqueria Market, beside the Rambla, stands on the site occupied successively by the monastery of Santa Maria de Jerusalem (14th century) and the monastery of Sant Josep (16th century). The Gothic convent of Santa Caterina, which was destroyed by fire in 1835 and demolished two years later, lent its site and name to a market that has now been thoroughly remodelled and reconstructed. Even the Liceu Opera House was built on the site of a former Discalced Trinitarian monastery. The other great centre of music of Barcelona, the Palau de la Música Catalana, was built on the ruins of the monastery of Sant Francesc de Paula.

Here we may take a small detour to number 8 of Carrer Escudillers, in order to see the Grill Room, an old Modernista restaurant and cafe (for more information, see Let’s go out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants.”)

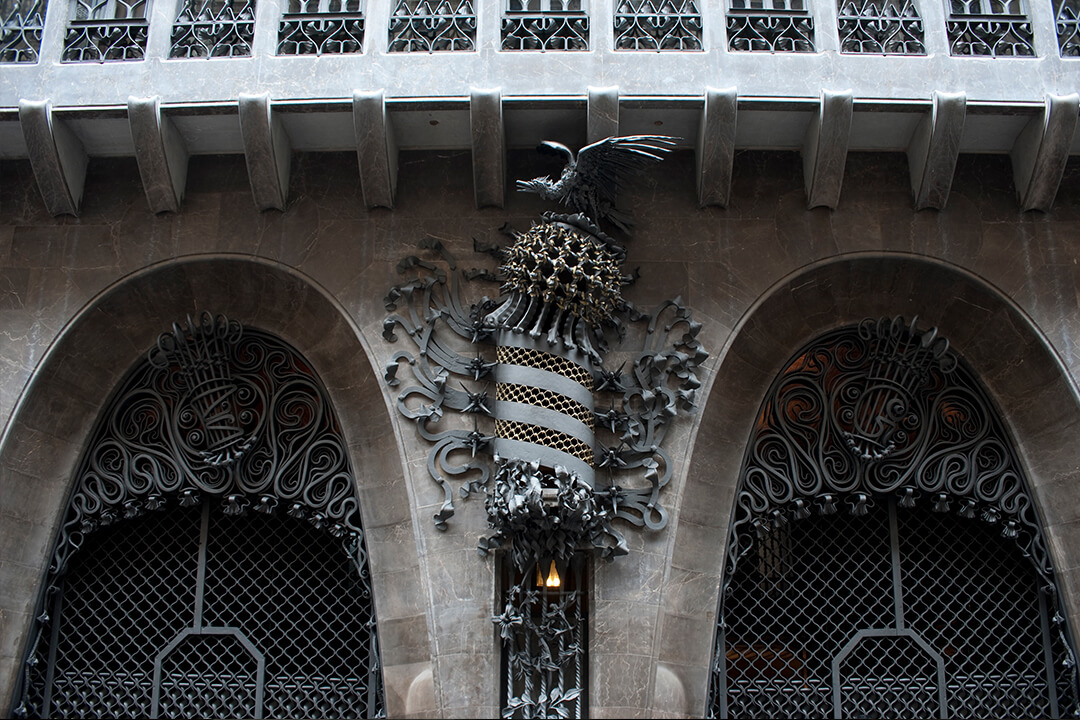

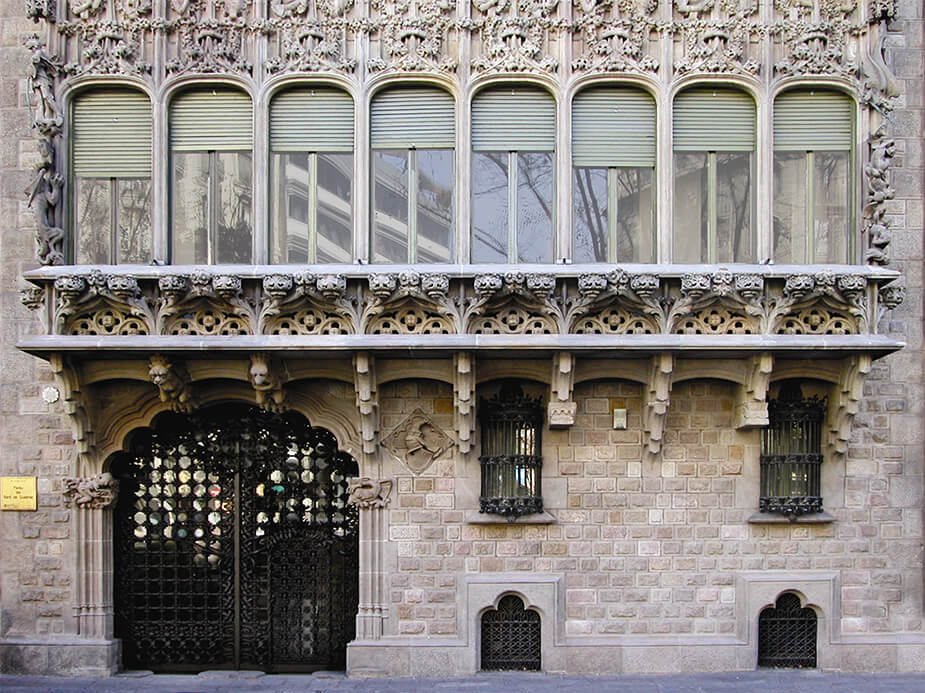

On leaving the square you will come to La Rambla, the famous main artery of Barcelona life. At the time of maximum splendour of the Modernista movement, little development land was available in the old part of Barcelona. Therefore, with the exception of a few shops in the Modernista style, there are few examples in this area of the city. However, these include masterpieces such as the ![]() PALAU GÜELL (8) (GÜELL PALACE. Nou de la Rambla, 3-5), the first work (1885-1889) that Antoni Gaudí, the most peculiar and striking architect of the Modernista movement, would offer the city of Barcelona, and now listed World Heritage by UNESCO. Gaudí was only 34 years old when he received the commission to build the private residence of the Güell family. And curiously it was not in the Eixample, which was already in full expansion, but in the Raval, a degraded zone that in the late 19th century had been taken over by prostitution and was full of brothels. Perhaps it was not very logical that Eusebi Güell, with seven children, should choose to live there, but he had a reason for doing so. His father, Joan Güell, lived in the Rambla and Eusebi bought the site of the Palau Güell to be near him. Gaudí’s aristocratic patron gave the architect a free budget to build a sumptuous, original palace in which to hold political meetings and chamber music concerts and to accommodate the most illustrious guests of the family. No sooner said than done. Gaudí used the best materials of the time and the construction costs soared. The final result was a masterpiece in Gaudí’s darkest style. Far from satisfying the bourgeois idea of comfort (it is a very tall building which was then without heating, so it must have been rather uncomfortable in winter), Gaudí’s Palau Güell is an unusual space featuring a magnificent, skilfully crafted interplay of volumes and light.

PALAU GÜELL (8) (GÜELL PALACE. Nou de la Rambla, 3-5), the first work (1885-1889) that Antoni Gaudí, the most peculiar and striking architect of the Modernista movement, would offer the city of Barcelona, and now listed World Heritage by UNESCO. Gaudí was only 34 years old when he received the commission to build the private residence of the Güell family. And curiously it was not in the Eixample, which was already in full expansion, but in the Raval, a degraded zone that in the late 19th century had been taken over by prostitution and was full of brothels. Perhaps it was not very logical that Eusebi Güell, with seven children, should choose to live there, but he had a reason for doing so. His father, Joan Güell, lived in the Rambla and Eusebi bought the site of the Palau Güell to be near him. Gaudí’s aristocratic patron gave the architect a free budget to build a sumptuous, original palace in which to hold political meetings and chamber music concerts and to accommodate the most illustrious guests of the family. No sooner said than done. Gaudí used the best materials of the time and the construction costs soared. The final result was a masterpiece in Gaudí’s darkest style. Far from satisfying the bourgeois idea of comfort (it is a very tall building which was then without heating, so it must have been rather uncomfortable in winter), Gaudí’s Palau Güell is an unusual space featuring a magnificent, skilfully crafted interplay of volumes and light.

The façade of the Palau Güell, with evocative Venetian lines, is built with a stone of severe appearance, which highlights the wrought iron design covering the tympana of the two parabolic entrance and exit arches and forming the majestic coat of arms with the Catalan emblem, conceived as a small colonnade. The first area of the palace is the 20 metre-high foyer that gives the building a transparent appearance and articulates the different spaces into which this magnificent early work by Gaudí is divided. The whole building is organised around the central foyer. A majestic staircase leads to the authentic jewel in the crown of the Palau Güell: its surprising, mysterious, telluric central hall rising seven stories and crowned by a parabolic, cone-shaped dome. The dome is perforated by a series of small openings arranged in a circle that filter gentle indirect light, giving the hall a curious appearance that some experts liken to a planetarium in daylight and others to the central hall of an Arab hammam.

The roof terrace has twenty chimneys designed by Gaudí and restored between 1988 and 1992 by a group of artists who rebuilt the eight that had been most damaged, observing respect for Gaudí’s original work (on one of these new chimneys, however, with a little patience one can find Cobi, the Olympic mascot dog of Barcelona ‘92, depicted among the trencadís). This was the first work in which Gaudí used trencadís, a facing technique of Arabic origin using irregular tile fragments, which Gaudí and the Modernista movement adopted as one their characteristic features. The Gaudinian chimneys, all unique and different as if they were different sketches of an idealised model, probably represent one of the first drafts of the design that Gaudí would culminate years later on the roof terrace of La Pedrera. With a little imagination they recall a group of trees. On one of them, which is totally white and was probably the last one built by Gaudí, the small green stamp of a pottery manufacturer of Limoges can be seen. The legend goes that Eusebi Güell had a marvellous dinner service from Limoges that he was tired of, and he gave them to the architect for use in the cladding of the last chimney of the Palau.

The basement is a peculiar crypt of very low vaults supported by simple fungiform columns, a spectacular work of architecture which formerly housed the stables and the grooms’ quarters. The brick columns and their capitals form one of the most enigmatic, evocative and best-known landscapes of Gaudí’s architecture. Though it was conceived as a family residence, the Palau Güell was used for this purpose for only a few years. The Güell family lived in it until the Spanish Civil War (1936-39), when the palace was confiscated by the anarchist trade unions CNT-FAI, which turned it into a barracks and prison. The Güells never returned. The general abandon and deterioration of this area of the Raval led the heirs of Count Güell to decide, in 1945, to transfer the palace to the Barcelona Provincial Council, its current owner.

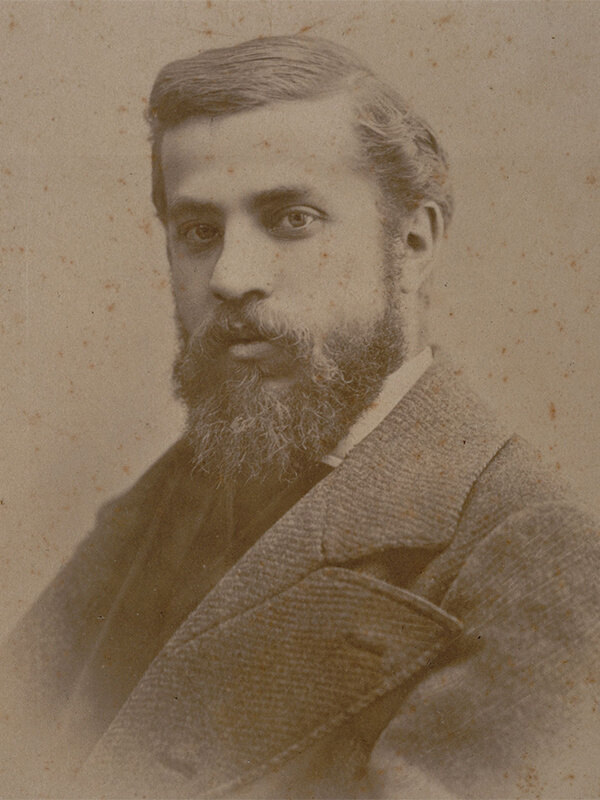

Antoni Gaudí i Cornet

1852 - 1926

Antoni Gaudí i Cornet was born in 1852 in Reus to a family of coppersmiths from Riudoms. The smallest of five brothers, he moved to Barcelona in 1873 to study architecture, which he finished four years later. It is said that on awarding him his degree, the Director of the School of Architecture, Elies Rogent, muttered “Who knows whether we have given the degree to a madman or a genius: only time will tell”.

His first professional assignment was to design the new buildings of the textile cooperative of Mataró (1878), for which Gaudí conceived unusual catenary arches of wood and a giant bronze bee (symbol of the cooperative). In the same year, he designed a glass and crystal ware cabinet decorated with wrought-iron, mahogany and marquetry for a Catalan glove manufacturer, Esteban Cornellá, to display his products at the Universal Exhibition of Paris. The display cabinet seduced Eusebi Güell, an industrialist, aristocrat and rising politician, who was to become the patron of the young architect. Gaudí’s first commission for Güell was to design the furniture of the pantheon that the Marquis of Comillas, Güell’s all-powerful father-in-law, possessed on the outskirts of Santander. This assignment was followed by another, a pergola decorated with globes and hundreds of glass pieces. From then on his career and his work, which in the course of time became one of the most famous symbols of Barcelona, were intimately linked to the Güell family.

In 1883 the Church commissioned him to build the Sagrada Família, which was to become the great work of his life, and in which he invested all the efforts of his last years. This gradual concentration on the great expiatory temple ran parallel to the consolidation of a fervent Catholicism, an aspect which had not been apparent in the young Gaudí. In his maturity, the great Catalan architect was known to be a frugal and solitary man who devoted all his energy to the profession through which he expressed his two great passions: Christianity and Catalan nationalism. His obstinate defence of Catalan identity even led to his arrest by the police in 1924 on Catalan National day (11th September), for refusing to submit to an officer who ordered him to speak in Spanish.

On 7th June 1926, Gaudí was hit by a tram when he was crossing the Gran Via. Initially on his admission the staff of the hospital, who struggled to save his life for three days, took him for a beggar because of his humble attire.

Not far from Palau Güell up Carrer Nou de la Rambla is the ![]() (9) (Nou de la Rambla, 34), a Modernista bar that has been open for almost a century, since 1910 (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants).

(9) (Nou de la Rambla, 34), a Modernista bar that has been open for almost a century, since 1910 (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants).

The Barcelona Modernisme Route continues up the Rambla towards Plaça de Catalunya. Almost opposite Plaça Reial’s porticos is the HOTEL ORIENTE (Rambla, 45-47), built in 1842 when the old religious school of Sant Bonaventura was converted into a thriving inn. The hotel, which remodelled its façade in 1881, preserves in its ballroom the magnificent structure of a 17th-century cloister with square pillars and an old rectangular refectory covered with a vault. It has accommodated such distinguished guests as the writer Hans Christian Andersen, the American actor Errol Flynn, the bullfighter Manolete and the soprano Maria Callas. Its discreet façade features the sculptures of two angels standing above the arch of the main entrance.

Continuing up the Rambla one comes to one of the most emblematic buildings of the city, though it is not in the Modernista style: the ![]() GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU (LICEU OPERA HOUSE. Rambla, 51-65). The history of this emblem of Barcelona has been marked by fire. The original opera house, built by Miquel Garriga in 1847 on the site of a Trinitarian monastery, was burnt down in 1861 and rebuilt by Josep Oriol Mestres. On the exterior, its simplicity is only broken by its characteristic façade with a central body of three large windows, but on the interior it is one of the most lavishly decorated opera houses in the world. After the theatre burnt down again in 1994, it was rebuilt once more, this time by the architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales, who restored it to its original lavish style and recovered the rooms with trompe l’oeil and Pompeiian paintings. In its first period as an opera house, the Liceu had to compete with the TEATRE PRINCIPAL (Rambla, 27), which had a capacity for 2,000 persons and a long tradition in the city. The Liceu, which raised the first curtain with Anna Bolena by Donizetti, came out the winner, becoming a cathedral of good taste and the favourite showcase for the more opulent classes of Barcelona to display their wealth. Despite the sobriety of its architecture, it features a canopy of wrought iron over the main entrance and sgraffito work that pays homage to Calderón de la Barca, Mozart, Rossini and Moratín. Almost at the corner of the Rambla and Carrer Sant Pau, the building of the Liceu houses a truly elitist sanctuary: the Cercle del Liceu, a traditional and aristocratic private institution, an old club in the purest English style, which conceals in its inner rooms memorable works by the Modernista painters Ramon Casas and Alexandre de Riquer, in addition to stained glass decorated with Wagnerian themes by Oleguer Junyent.

GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU (LICEU OPERA HOUSE. Rambla, 51-65). The history of this emblem of Barcelona has been marked by fire. The original opera house, built by Miquel Garriga in 1847 on the site of a Trinitarian monastery, was burnt down in 1861 and rebuilt by Josep Oriol Mestres. On the exterior, its simplicity is only broken by its characteristic façade with a central body of three large windows, but on the interior it is one of the most lavishly decorated opera houses in the world. After the theatre burnt down again in 1994, it was rebuilt once more, this time by the architect Ignasi de Solà-Morales, who restored it to its original lavish style and recovered the rooms with trompe l’oeil and Pompeiian paintings. In its first period as an opera house, the Liceu had to compete with the TEATRE PRINCIPAL (Rambla, 27), which had a capacity for 2,000 persons and a long tradition in the city. The Liceu, which raised the first curtain with Anna Bolena by Donizetti, came out the winner, becoming a cathedral of good taste and the favourite showcase for the more opulent classes of Barcelona to display their wealth. Despite the sobriety of its architecture, it features a canopy of wrought iron over the main entrance and sgraffito work that pays homage to Calderón de la Barca, Mozart, Rossini and Moratín. Almost at the corner of the Rambla and Carrer Sant Pau, the building of the Liceu houses a truly elitist sanctuary: the Cercle del Liceu, a traditional and aristocratic private institution, an old club in the purest English style, which conceals in its inner rooms memorable works by the Modernista painters Ramon Casas and Alexandre de Riquer, in addition to stained glass decorated with Wagnerian themes by Oleguer Junyent.

On the other side of the street, the route comes to an establishment with a long tradition that has Modernista decoration on the façade, ![]() CAMISERIA BONET (10) (BONET OUTFITTER’S. Rambla, 72), a former outfitter’s shop founded in 1890, which changed ownership in 2002, and now sells mainly Barcelona souvenirs, but has kept its outer decoration virtually untouched. In the adjoining building is the

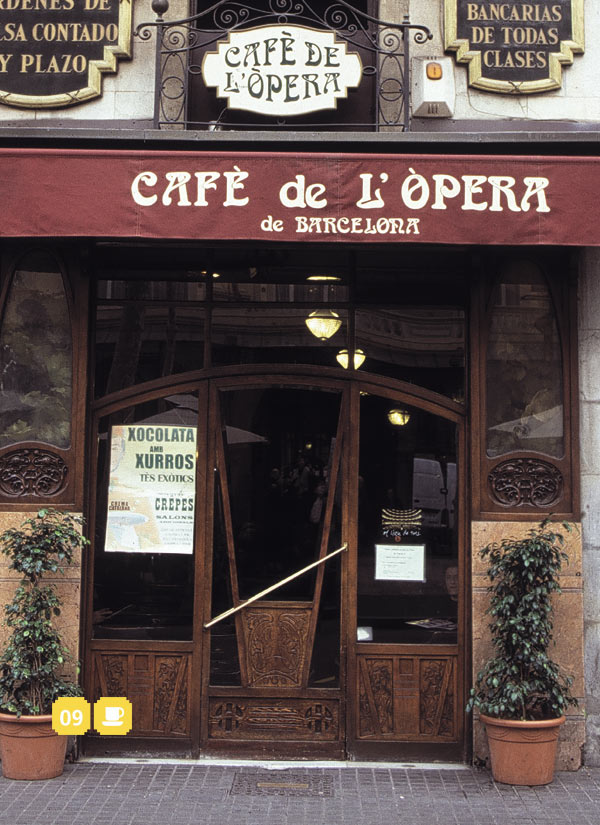

CAMISERIA BONET (10) (BONET OUTFITTER’S. Rambla, 72), a former outfitter’s shop founded in 1890, which changed ownership in 2002, and now sells mainly Barcelona souvenirs, but has kept its outer decoration virtually untouched. In the adjoining building is the ![]() CAFÈ DE L’ÒPERA (11)(Rambla, 74), a café with a cosy atmosphere opened in 1929 on the premises of the former La Mallorquina chocolate shop. Featuring inside, the well-preserved original furniture: the Thonet chairs and the nineteenth-century mirrors with female figures suggesting characters from different operas (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants)

CAFÈ DE L’ÒPERA (11)(Rambla, 74), a café with a cosy atmosphere opened in 1929 on the premises of the former La Mallorquina chocolate shop. Featuring inside, the well-preserved original furniture: the Thonet chairs and the nineteenth-century mirrors with female figures suggesting characters from different operas (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants)

After the Liceu, on the left, the route leaves La Rambla momentarily to make a detour down Carrer Sant Pau. The history of hotels in Barcelona would be incomplete without the ![]() HOTEL ESPAÑA (12) (Sant Pau, 9-11), one of its oldest establishments. The main architectural interest of this hotel, which formerly accommodated the Philippine national hero José Rizal, lies in its public rooms, decorated in 1902-1903 by one of the fathers of Modernisme, Lluís Domènech i Montaner. In the Hotel España, Domènech i Montaner worked with two great masters of the plastic arts of the time: the sculptor Eusebi Arnau and the painter Ramon Casas. Eusebi Arnau made the splendid alabaster chimney in one of the dining rooms, which is visible from the street, and Ramon Casas did the marine sgraffito work in the interior dining room, which also features a coffered skylight that casts gentle lighting on Casas’s work. Domènech i Montaner completed the work with two ingenious wooden wainscots. One of them, of meticulous design, is decorated with blue tiles representing the Spanish provinces, whereas the other, of Roman type, depicts floral themes (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants). A few steps from the Hotel España there is another hotel with touches of Modernisme: the

HOTEL ESPAÑA (12) (Sant Pau, 9-11), one of its oldest establishments. The main architectural interest of this hotel, which formerly accommodated the Philippine national hero José Rizal, lies in its public rooms, decorated in 1902-1903 by one of the fathers of Modernisme, Lluís Domènech i Montaner. In the Hotel España, Domènech i Montaner worked with two great masters of the plastic arts of the time: the sculptor Eusebi Arnau and the painter Ramon Casas. Eusebi Arnau made the splendid alabaster chimney in one of the dining rooms, which is visible from the street, and Ramon Casas did the marine sgraffito work in the interior dining room, which also features a coffered skylight that casts gentle lighting on Casas’s work. Domènech i Montaner completed the work with two ingenious wooden wainscots. One of them, of meticulous design, is decorated with blue tiles representing the Spanish provinces, whereas the other, of Roman type, depicts floral themes (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants). A few steps from the Hotel España there is another hotel with touches of Modernisme: the ![]() HOTEL PENINSULAR (13) (Sant Pau, 36). The main interest of this building, a former religious school, lies in its court with galleries and a skylight that enhances the green and cream colours of the walls.

HOTEL PENINSULAR (13) (Sant Pau, 36). The main interest of this building, a former religious school, lies in its court with galleries and a skylight that enhances the green and cream colours of the walls.

Back on La Rambla, the Route comes to Pla de la Boqueria, presided over by the MOSAIC CERÀMIC DE JOAN MIRÓ (CERAMIC MOSAIC BY JOAN MIRÓ) placed here by the City Council in 1976, which in the course of time has become an emblematic image of the most popular street in Barcelona. Close by on the right you will find the CASA BRUNO CUADROS (BRUNO CUADROS HOUSE. Rambla, 82), a very interesting pre-Modernista building by Josep Vilaseca, the designer the Triumphal Arch of 1888. This ancient house, known popularly as “the Umbrella House”, was restored in 1883, incorporating oriental features such as the decoration of the façade with sgraffito work and stained glass, the Egyptian-style gallery on the first floor and the Chinese dragon that protrudes from the corner of the building. The old shop of the building, today occupied by a bank, has ornamental elements of Japanese inspiration in wood, glass and wrought iron.

La Rambla

The original Rambla was a wide, rambling path that ran down the southern limits of the city parallel to the medieval wall built by king James 1st in the 13th century. One hundred years later a new wall would surround the Raval and leave the Rambla wall enclosed, without its theoretical defensive function. However, the wall gates (Santa Anna, Portaferrissa, Boqueria, Trentaclaus and Framenors) did not disappear and continued to be meeting points for open air markets, or were “recycled” into new buildings, such as a cannon factory. “Rambla”, in Arabic, means “watercourse” and this is precisely what it was: a torrent, known as the Cagalell, which had become both the sewer and the moat of the city. In the 16th century, the first religious centres (Convent de Sant Josep, 1586), schools (Estudis Generals, 1536) and theatres (Teatro de la Santa Creu, 1597) began to appear on the southern bank. Thus the 17th-century Rambla had the city wall on one side and churches and convents on the other side, in what is now the Raval district. In the late 18th century, military engineers under Juan M. Cermeño transformed this wide ditch into an elegant avenue, channelling the stream under ground and clearing plots for new, aligned buildings.

There is only one Rambla, but each section has been given a different name: going up from the port you will walk along Rambla de Santa Mònica, Rambla dels Caputxins, Rambla de Sant Josep, Rambla dels Estudis and Rambla de Canaletes. These names are not gratuitous but correspond to the monasteries, churches or buildings that stood beside the avenue that began to take shape as the ditch was filled in. In 1768 old king James’s wall was demolished and work began on the construction of some of the most emblematic buildings, such as Palau de la Virreina and Palau Moja, which are on the Modernisme Route path, and Casa March de Reus (built by Joan Soler i Faneca in 1780) which is left behind down the Rambla, at number 8. The last great transformation of the Rambla was in the 19th century, when the disentailment of the church’s property as a result of liberal policies led to the disappearance of most monasteries that stood on it. They were replaced by new streets (Carrer Ferran), public spaces (Plaça Reial), markets (La Boqueria) and buildings that have become emblematic (Liceu). The Rambla is currently the best showcase of the city, of its history and of the life of its citizens, as was described by the Catalan writer Josep Pla in one of his works: “The Rambla is a marvel. It is one of the few streets of Barcelona in which I feel fully at ease. There are always enough people to meet someone you know, but there are always enough people to go unnoticed if you wish”.

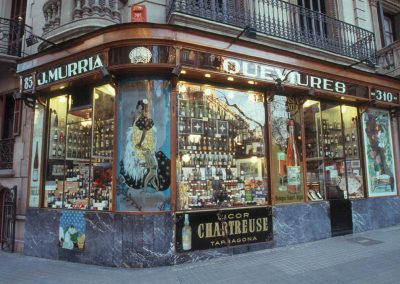

Many other shops in Barcelona had a similar fate to this one. In 1962, architect David John Mackay estimated that there were 800 Modernista shops in the city. With the passing of time and the relentless work of bulldozers, this number has now been reduced to about fifty. Day by day there are fewer survivors of this Modernisme that some have unjustly called “minor” only because it was smaller in size than the large works of architecture. Some of these shops have been conserved in their full splendour, whereas others survive as best they can in isolated locations of the city. Some are in good condition, others are in a pitiful state, but all have an artistic unity that allows one to reconstruct -surrounded by stucco, mosaic, stained glass and carved mahogany- those years between the Universal Exhibition of 1888 and the second decade of the 20th century. This was a time in which the bourgeoisie of Barcelona travelled to Paris and firmly believed that Catalonia was Europe, a time in which Modernisme became a daily presence and made works of art out of the most vulgar articles. The euphoria of the turn of the century, the desire for renewal, was translated into a social use of art, an anonymous and popular art that dignified any design. It thus came about that baker’s shops, cake shops, chemist’s, clothiers or perfumeries were treated with the same respect in their decoration as the mansions of the bourgeoisie. In addition to Casa Batlló, La Pedrera, Park Güell and the Sagrada Família, many small establishments wore the new Modernista style with pride. In 1909, the magazine L’Esquella de la Torratxa summarised in a single phrase the Modernista fever that was running through the city: “Barcelona is destined to be the Athens of Art Nouveau”. A selection of the best examples of Modernista shops still open nowadays can be found in this guide in the chapter “Forever Beautiful”.

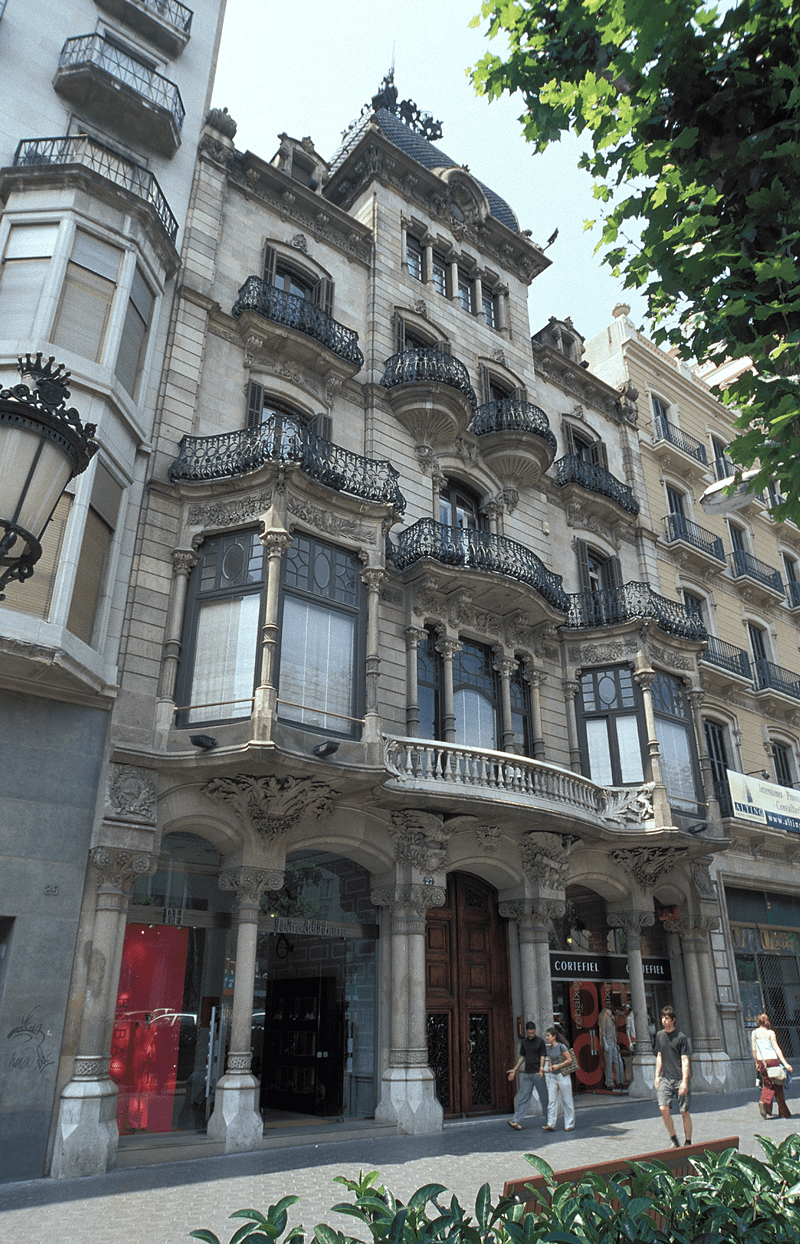

The best example of this Modernista fever that ran through Barcelona is provided by two almost adjoining buildings on the Rambla. ![]() (14) (DOCTOR GENOVÉ HOUSE. Rambla, 77) by Enric Sagnier i Villavecchia (1911) housed a chemist’s shop and its laboratory until 1974 (now replaced by a Basque tapes bar).

(14) (DOCTOR GENOVÉ HOUSE. Rambla, 77) by Enric Sagnier i Villavecchia (1911) housed a chemist’s shop and its laboratory until 1974 (now replaced by a Basque tapes bar).

Sagnier designed a building with a slightly Gothic appearance featuring a large central window, blue mosaics and a pointed entrance arch, with a magnificent relief of Aesculapius that recalls the original use of the building. Almost next to the former chemist’s shop is the ![]() ANTIGA CASA FIGUERAS (15)(FORMER FIGUERAS HOUSE. Rambla, 83), currently Pastisseria Escribà, a cake shop with an elaborate Modernista decoration by Antoni Ros i Güell (1902), with an abundance of mosaics, stucco, wrought iron, stained glass and wooden furniture in chocolate colour.

ANTIGA CASA FIGUERAS (15)(FORMER FIGUERAS HOUSE. Rambla, 83), currently Pastisseria Escribà, a cake shop with an elaborate Modernista decoration by Antoni Ros i Güell (1902), with an abundance of mosaics, stucco, wrought iron, stained glass and wooden furniture in chocolate colour.

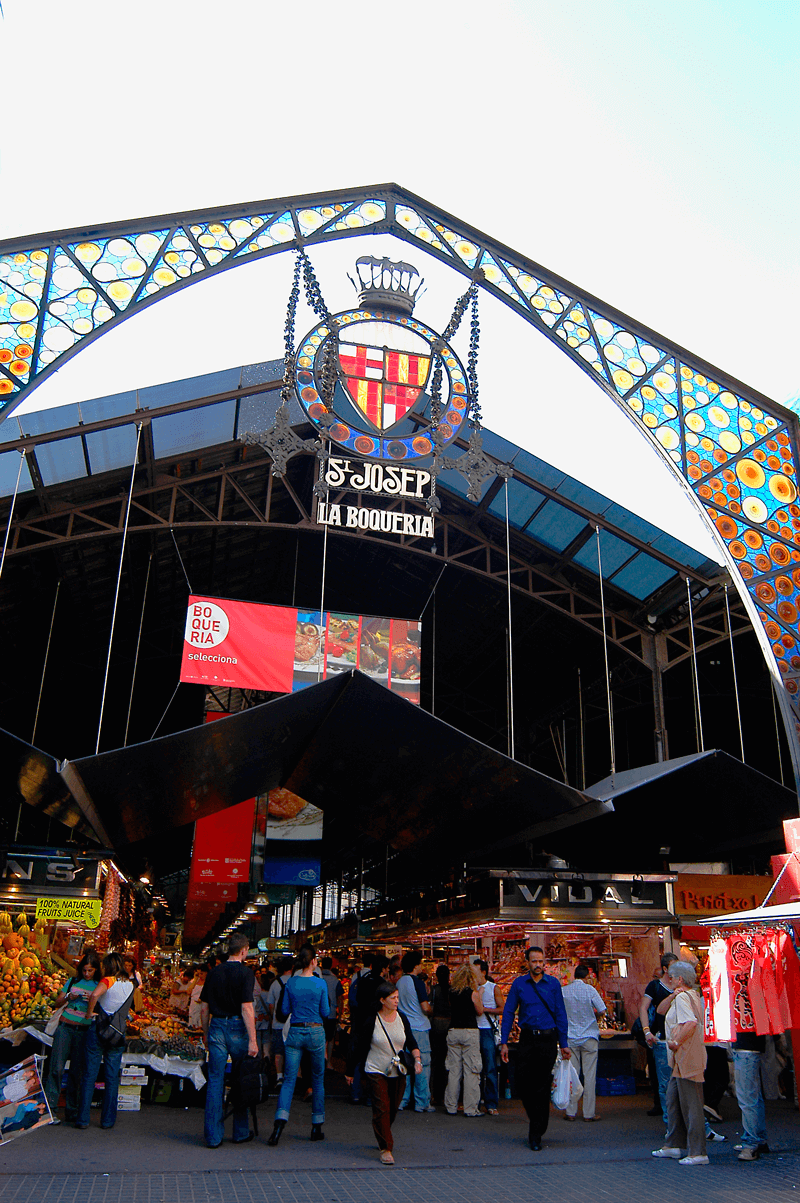

One does not have to walk too far to find the ![]() MERCAT DE LA BOQUERIA (16) (BOQUERIA MARKET. Rambla, 91), the oldest and most famous market in the city. From ancient times there had been, more or less in the same place, an open-air market in which the farmers from what is now the Raval district sold their products to the inhabitants of the walled city. Famous for the quality of its merchandise, the market occupies the former site of the Discalced Carmelite monastery of Sant Josep, which was burnt down in July 1835. The market was built five years later, in 1840, as a large porticoed square with Ionic columns under which the travelling tradesmen of the city could offer their varied products. A few years later, in 1914, an attractive metal roof designed by the engineer Miquel de Bergue was added. The market and its surroundings have been restored in recent years to the way they were in the early 20th century. The Boqueria is set in the central section of the Rambla-perhaps the most colourful and exuberant one: the Rambla de les Flors owes its name to the score of flower stalls that have been open all year round since Corpus Christi Day in 1853.

MERCAT DE LA BOQUERIA (16) (BOQUERIA MARKET. Rambla, 91), the oldest and most famous market in the city. From ancient times there had been, more or less in the same place, an open-air market in which the farmers from what is now the Raval district sold their products to the inhabitants of the walled city. Famous for the quality of its merchandise, the market occupies the former site of the Discalced Carmelite monastery of Sant Josep, which was burnt down in July 1835. The market was built five years later, in 1840, as a large porticoed square with Ionic columns under which the travelling tradesmen of the city could offer their varied products. A few years later, in 1914, an attractive metal roof designed by the engineer Miquel de Bergue was added. The market and its surroundings have been restored in recent years to the way they were in the early 20th century. The Boqueria is set in the central section of the Rambla-perhaps the most colourful and exuberant one: the Rambla de les Flors owes its name to the score of flower stalls that have been open all year round since Corpus Christi Day in 1853.

A few steps from the Boqueria one finds the ![]() PALAU DE LA VIRREINA (VICEREINE’S PALACE. Rambla, 99), built by Josep Ausich in 1778 for the former Viceroy of Peru, Manuel Amat i Junyent. The Viceroy never occupied the building because he died before it was finished. It was, however, occupied by his widow, the Vicereine María Francisca Fivaller, after whom the palace was named in the course of time. It was bought by the City Council in 1944 and in the late 1980s it became the offices of the Municipal Culture Area. The building is a good example of the French influence on architects of the 18th century. The imposing classical façade, sumptuous and Baroque in style, combines perfectly with a French-style Rococo decoration that finds its best example in the vaulted dining room illustrated with allegorical paintings. The remaining rooms in the building still have their original decoration, in Imperial style. The ground floor, which was formerly occupied by the amanuenses who wrote letters for the illiterate, currently houses a bookshop and a citizen’s information office. Next to it, on the ground floor of number 97, is the venerated music shop, CASA BEETHOVEN, founded in 1880 by the musical publisher Rafael Guàrdia.

PALAU DE LA VIRREINA (VICEREINE’S PALACE. Rambla, 99), built by Josep Ausich in 1778 for the former Viceroy of Peru, Manuel Amat i Junyent. The Viceroy never occupied the building because he died before it was finished. It was, however, occupied by his widow, the Vicereine María Francisca Fivaller, after whom the palace was named in the course of time. It was bought by the City Council in 1944 and in the late 1980s it became the offices of the Municipal Culture Area. The building is a good example of the French influence on architects of the 18th century. The imposing classical façade, sumptuous and Baroque in style, combines perfectly with a French-style Rococo decoration that finds its best example in the vaulted dining room illustrated with allegorical paintings. The remaining rooms in the building still have their original decoration, in Imperial style. The ground floor, which was formerly occupied by the amanuenses who wrote letters for the illiterate, currently houses a bookshop and a citizen’s information office. Next to it, on the ground floor of number 97, is the venerated music shop, CASA BEETHOVEN, founded in 1880 by the musical publisher Rafael Guàrdia.

Continuing up the Rambla we find one of the most attractive Romantic buildings in the city, ![]() CASA FRANCESC PIÑA (FRANCESC PIÑA HOUSE. Rambla, 105), also known as “El Regulador” after the jeweller’s shop that occupies the ground floor, today Joieria Bagués. This building by Josep Fontserè (1850) has a terra cotta and white-painted façade with pink stucco work, featuring false columns with capitals and bas-reliefs decorating the upper floors.

CASA FRANCESC PIÑA (FRANCESC PIÑA HOUSE. Rambla, 105), also known as “El Regulador” after the jeweller’s shop that occupies the ground floor, today Joieria Bagués. This building by Josep Fontserè (1850) has a terra cotta and white-painted façade with pink stucco work, featuring false columns with capitals and bas-reliefs decorating the upper floors.

At the corner of Carrer del Carme, you will find the ![]() ESGLÉSIA DE BETLEM (CHURCH OF BETHLEHEM. Rambla, 107), built between 1680 and 1732 by Josep Juli. It is one of the few examples of Baroque art in Barcelona, but in its structure it remains faithful to the precepts of previous Catalan Gothic architecture, with a wide single nave flanked by chapels. Of the doors giving onto the Rambla, one was designed by Francesc Santacruz in 1690 and portrays Christ the Child; the other, portraying Saint John the Baptist, was designed in 1906 by Enric Sagnier taking Santacruz’s work as a reference. The church that can be seen today is not as sumptuous as it was before the Civil War of 1936-39, when its polychrome work, carvings, Italian stuccos and marbles were irreparably damaged. Since 1952, the church has kept an image of Our Lady of the Foresaken, by Mariano Benlliure. On the opposite side of the street is the

ESGLÉSIA DE BETLEM (CHURCH OF BETHLEHEM. Rambla, 107), built between 1680 and 1732 by Josep Juli. It is one of the few examples of Baroque art in Barcelona, but in its structure it remains faithful to the precepts of previous Catalan Gothic architecture, with a wide single nave flanked by chapels. Of the doors giving onto the Rambla, one was designed by Francesc Santacruz in 1690 and portrays Christ the Child; the other, portraying Saint John the Baptist, was designed in 1906 by Enric Sagnier taking Santacruz’s work as a reference. The church that can be seen today is not as sumptuous as it was before the Civil War of 1936-39, when its polychrome work, carvings, Italian stuccos and marbles were irreparably damaged. Since 1952, the church has kept an image of Our Lady of the Foresaken, by Mariano Benlliure. On the opposite side of the street is the ![]() PALAU MOJA (MOJA PALACE. Rambla, 118), an old property of the Marquis of Comillas built between 1774 and 1789 by the Mas i Dordal brothers, when the Rambla was transformed into an avenue. The long façade, decorated with ochre and reddish bays, rises above a portico and has a simple central pediment. The building, decorated with paintings by the Neo-Classical painter Francesc Pla, “El Vigatà”, still has the original furniture and the room occupied by the catalan “national poet” Jacint Verdaguer, a protégé of the Marquise. The Comillases were related to the Güells, and they also occasionally commissioned works from Gaudí, who thus became acquainted with Verdaguer and even -as in the Pavellons Güell, number (90) of the Modernisme Route- used his poetry as an inspiration. The palace currently houses premises of the Culture Department of the Generalitat, the autonomous Catalan government.

PALAU MOJA (MOJA PALACE. Rambla, 118), an old property of the Marquis of Comillas built between 1774 and 1789 by the Mas i Dordal brothers, when the Rambla was transformed into an avenue. The long façade, decorated with ochre and reddish bays, rises above a portico and has a simple central pediment. The building, decorated with paintings by the Neo-Classical painter Francesc Pla, “El Vigatà”, still has the original furniture and the room occupied by the catalan “national poet” Jacint Verdaguer, a protégé of the Marquise. The Comillases were related to the Güells, and they also occasionally commissioned works from Gaudí, who thus became acquainted with Verdaguer and even -as in the Pavellons Güell, number (90) of the Modernisme Route- used his poetry as an inspiration. The palace currently houses premises of the Culture Department of the Generalitat, the autonomous Catalan government.

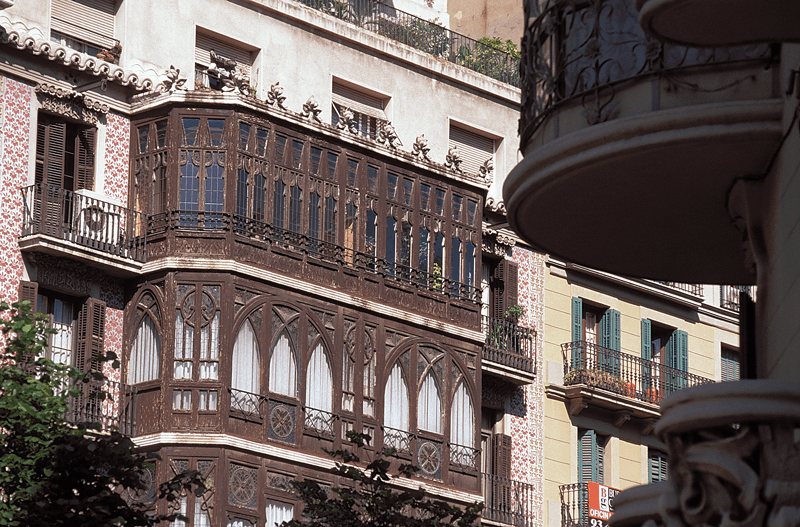

A small detour from the main route leads you up Carrer del Carme, which conceals two Modernista treasures only a few metres from the Rambla: the popular store ![]() EL INDIO (17) (Carme, 24), decorated in 1922 by Vilaró i Valls in the purest Modernista style, and further along, the

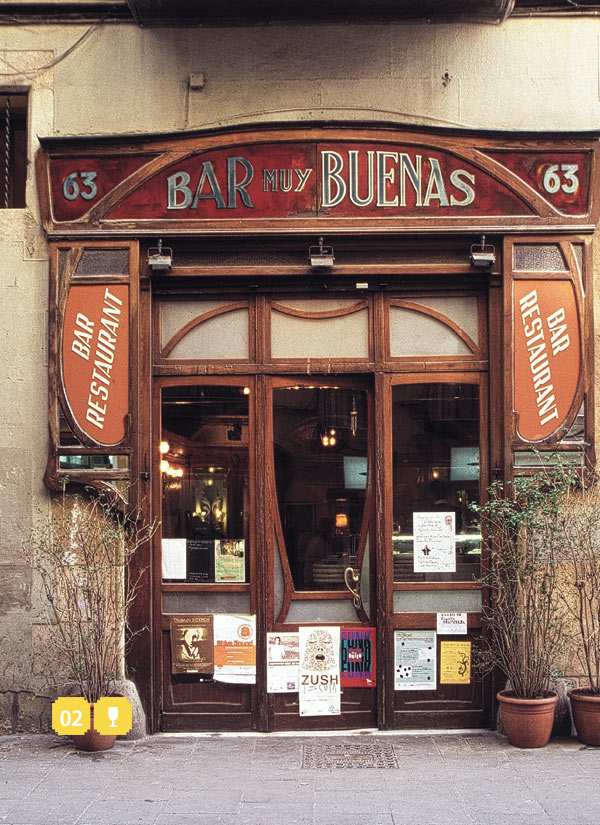

EL INDIO (17) (Carme, 24), decorated in 1922 by Vilaró i Valls in the purest Modernista style, and further along, the ![]() MUY BUENAS (18) (Carme, 63), an establishment with a Modernista façade of wood that still has part of its original furniture, such as the old marble bar, which is over a century old (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants).

MUY BUENAS (18) (Carme, 63), an establishment with a Modernista façade of wood that still has part of its original furniture, such as the old marble bar, which is over a century old (for further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants).

The route continues up La Rambla, known here as “Rambla dels Ocells” (Rambla of the Birds), because of the stalls selling pets that alternate with the popular newsstands of La Rambla. On the way to Plaça de Catalunya, the route has two important sites. The first is the ![]() REIAL ACADÈMIA DE CIÈNCIES I ARTS (19) (ROYAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS. Rambla, 115), built in 1883 by Josep Domènech i Estapà on the ruins of a former Jesuit school. In this building the architect was a pioneer in the use of ornamental and stylistic resources that would be such a success years later in the Modernista movement. As well as the Reial Acadèmia, the building currently houses the Poliorama Theatre and the Viena restaurant, the former Casa Mumbrú. Its most distinguishing feature is the clock on the façade that is popularly acknowledged to set the official time of Barcelona. Another element of interest on the façade is its elegant bay window. The dome and domed tower that crown the building originally housed a meteorological and astronomical observatory. The second site is the FARMÀCIA NADAL (NADAL PHARMACY. Rambla, 121), a chemist’s shop dating from 1850 when it was opened as Farmàcia Masó, which was later transformed into a charming shop featuring multi-coloured mosaics and four red advertising lamps, a good example of Noucentisme (a post-Modernista neoclassical movement).

REIAL ACADÈMIA DE CIÈNCIES I ARTS (19) (ROYAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS. Rambla, 115), built in 1883 by Josep Domènech i Estapà on the ruins of a former Jesuit school. In this building the architect was a pioneer in the use of ornamental and stylistic resources that would be such a success years later in the Modernista movement. As well as the Reial Acadèmia, the building currently houses the Poliorama Theatre and the Viena restaurant, the former Casa Mumbrú. Its most distinguishing feature is the clock on the façade that is popularly acknowledged to set the official time of Barcelona. Another element of interest on the façade is its elegant bay window. The dome and domed tower that crown the building originally housed a meteorological and astronomical observatory. The second site is the FARMÀCIA NADAL (NADAL PHARMACY. Rambla, 121), a chemist’s shop dating from 1850 when it was opened as Farmàcia Masó, which was later transformed into a charming shop featuring multi-coloured mosaics and four red advertising lamps, a good example of Noucentisme (a post-Modernista neoclassical movement).

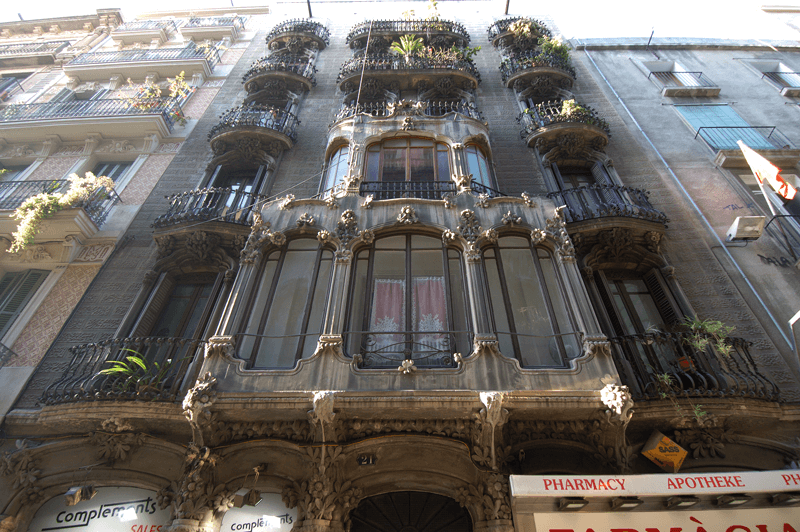

Crossing the Rambla, we find Carrer Canuda and Carrer Santa Anna. A short way into Santa Anna is ![]() CASA ELENA CASTELLANO (20) (Santa Anna, 21), a 1907 building by Jaume Torres i Grau, a typical Modernista house with its bay windows and floral ornaments. Back to Carrer Canuda, after a few metres you will find the former PALAU SABASSONA of medieval origin. Since 1836 this building is the

CASA ELENA CASTELLANO (20) (Santa Anna, 21), a 1907 building by Jaume Torres i Grau, a typical Modernista house with its bay windows and floral ornaments. Back to Carrer Canuda, after a few metres you will find the former PALAU SABASSONA of medieval origin. Since 1836 this building is the ![]() ATENEU BARCELONÈS (21) (Canuda, 6), one of the emblematic cultural entities of the city. Three small jewels remain from Josep Maria Jujol i Gibert and Josep Font i Gumà’s 1906 Modernista remodelling : the lift cabin, one of the first to be installed in the city; the reading rooms of the library; and the Romantic-style hanging garden. Continuing down Carrer Canuda you will come to Plaça de la Vila de Madrid, where you can see the remains of a Roman necropolis discovered in 1954 during the redevelopment of the site of the former Discalced Carmelite monastery that had been demolished after the Civil War. The square, redeveloped in 2003, stands on an old Roman access road to the city, and a small section of the original paving can still be seen. The road was flanked by the remains of monolithic funerary monuments and modest tegulae. Carrer Canuda leads into Portal de l’Àngel. A few metres to the left is the building of a gas company,

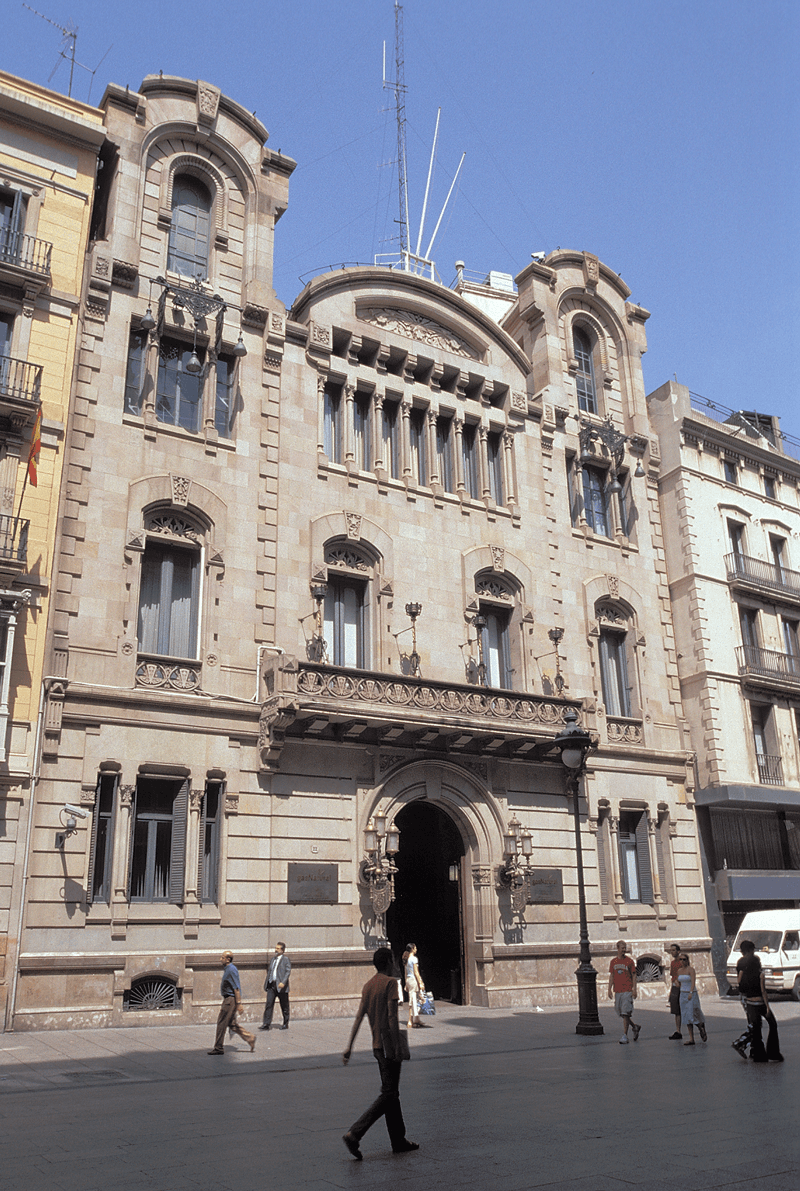

ATENEU BARCELONÈS (21) (Canuda, 6), one of the emblematic cultural entities of the city. Three small jewels remain from Josep Maria Jujol i Gibert and Josep Font i Gumà’s 1906 Modernista remodelling : the lift cabin, one of the first to be installed in the city; the reading rooms of the library; and the Romantic-style hanging garden. Continuing down Carrer Canuda you will come to Plaça de la Vila de Madrid, where you can see the remains of a Roman necropolis discovered in 1954 during the redevelopment of the site of the former Discalced Carmelite monastery that had been demolished after the Civil War. The square, redeveloped in 2003, stands on an old Roman access road to the city, and a small section of the original paving can still be seen. The road was flanked by the remains of monolithic funerary monuments and modest tegulae. Carrer Canuda leads into Portal de l’Àngel. A few metres to the left is the building of a gas company, ![]() CATALANA DE GAS, GAS NATURAL (22) (Portal de l’Àngel, 20-22), a monumental and eclectic building designed by Josep Domènech i Estapà (1895). It was originally built for the Societat Catalana per a l’Enllumenat del Gas, and now contains an interesting Gas Museum exhibiting equipment that shows the evolution of technology for this energy source (tel.: 900 150 366, visits must be booked in advance).

CATALANA DE GAS, GAS NATURAL (22) (Portal de l’Àngel, 20-22), a monumental and eclectic building designed by Josep Domènech i Estapà (1895). It was originally built for the Societat Catalana per a l’Enllumenat del Gas, and now contains an interesting Gas Museum exhibiting equipment that shows the evolution of technology for this energy source (tel.: 900 150 366, visits must be booked in advance).

Going back down Portal de l’Àngel and turning into the small Carrer Montsió, after a few metres you will come to the popular Modernista tavern ![]() ELS QUATRE GATS (23) (Montsió, 3 bis. For further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants). This old bar was one of the artistic and cultural centres of the late 19th and early 20th century Barcelona. Ramon Casas, Santiago Rusiñol and Pablo Picasso are some of the illustrious characters who dined, drank and held their artistic gatherings in this unusual bar, which opened in 1897 on the ground floor of the Neo-Gothic CASA MARTÍ by Josep Puig i Cadafalch (1896). The building, which looks more European than Catalan in style, features large Gothic-style stained glass windows, a curious decoration on the windows and a Flamboyant-style balcony. The exterior also features sculptures by Eusebi Arnau, wrought iron work by Manuel Ballarín and -in the niche on the corner-Llimona’s sculpture of Saint Joseph. What you see now is a replica installed by the City Council in 2000: the original was destroyed during the Spanish Civil War. The inside is no less impressive. Ramon Casas paid for the circular chandeliers and the medieval furniture designed by Puig i Cadafalch. Another of his “gifts” was the painting depicting two men, Pere Romeu, the owner of the bar, and the artist himself riding a tandem; the one currently on display in the establishment is a copy, the original is in the MNAC museum (number (34) of the Route). The establishment, which even published its own magazine named Pèl i Ploma (Hair and Quill), became the haven of artists and intellectuals such as the composers Enric Granados and Isaac Albéniz, and the young painters Joaquim Mir and Pablo Picasso. Unfortunately, the building has not been fully preserved. The original lintel of the door, by Puig i Cadafalch, disappeared in one of the many changes that the premises have undergone in its more than a hundred years of history.

ELS QUATRE GATS (23) (Montsió, 3 bis. For further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants). This old bar was one of the artistic and cultural centres of the late 19th and early 20th century Barcelona. Ramon Casas, Santiago Rusiñol and Pablo Picasso are some of the illustrious characters who dined, drank and held their artistic gatherings in this unusual bar, which opened in 1897 on the ground floor of the Neo-Gothic CASA MARTÍ by Josep Puig i Cadafalch (1896). The building, which looks more European than Catalan in style, features large Gothic-style stained glass windows, a curious decoration on the windows and a Flamboyant-style balcony. The exterior also features sculptures by Eusebi Arnau, wrought iron work by Manuel Ballarín and -in the niche on the corner-Llimona’s sculpture of Saint Joseph. What you see now is a replica installed by the City Council in 2000: the original was destroyed during the Spanish Civil War. The inside is no less impressive. Ramon Casas paid for the circular chandeliers and the medieval furniture designed by Puig i Cadafalch. Another of his “gifts” was the painting depicting two men, Pere Romeu, the owner of the bar, and the artist himself riding a tandem; the one currently on display in the establishment is a copy, the original is in the MNAC museum (number (34) of the Route). The establishment, which even published its own magazine named Pèl i Ploma (Hair and Quill), became the haven of artists and intellectuals such as the composers Enric Granados and Isaac Albéniz, and the young painters Joaquim Mir and Pablo Picasso. Unfortunately, the building has not been fully preserved. The original lintel of the door, by Puig i Cadafalch, disappeared in one of the many changes that the premises have undergone in its more than a hundred years of history.

Continuing along Montsió, turn into Carrer de n’Amargós until Carrer Comtal, which takes you to Via Laietana, a wide avenue designed in the second half of the nineteenth century to open a direct access to the old port in an imitation of the North American business centres of the time. The development of this road took several decades, and masters of Modernisme like Domènech i Montaner and especially Puig i Cadafalch contributed to the project.

A short walk up Via Laietana takes us to the ![]() GREMI DELS VELERS (SAILMAKER’S GUILD, Via Laietana, 50), which is the local association of silk producers since 1764. This magnificent baroque building is decorated by sgraffito representing Atlantes and Cariatids. Slightly hidden behind it one of the essential jewels of Modernisme in Barcelona: the

GREMI DELS VELERS (SAILMAKER’S GUILD, Via Laietana, 50), which is the local association of silk producers since 1764. This magnificent baroque building is decorated by sgraffito representing Atlantes and Cariatids. Slightly hidden behind it one of the essential jewels of Modernisme in Barcelona: the ![]() PALAU DE LA MÚSICA CATALANA (24) (PALACE OF CATALAN MUSIC). The Palau de la Música was commissioned by the Orfeó Català choral music organisation to the architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner in 1904. The first stone of the new building was laid on Saint George’s day 1905 and the construction went on for three years. The result was a lavish concert hall for performances of Catalan choral music.

PALAU DE LA MÚSICA CATALANA (24) (PALACE OF CATALAN MUSIC). The Palau de la Música was commissioned by the Orfeó Català choral music organisation to the architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner in 1904. The first stone of the new building was laid on Saint George’s day 1905 and the construction went on for three years. The result was a lavish concert hall for performances of Catalan choral music.

The building was located on the site of the former monastery of Sant Francesc de Paula: the small site and the high price of the adjoining land at the time forced Domènech i Montaner to fit the auditorium into a tight grid of streets that limited the views from the exterior, and to find ingenious solutions to provide sufficient space for the stage and to include the offices and archives of the Orfeó in the building.

The church of the former monastery, converted into a parish church, survived until very recently, when it was demolished to provide more space for an extension of the Palau. This project, signed by Oscar Tusquets (2003), used the space to open a square which discovers the huge stained glass windows by Domènech, previously hidden behind the old church. This has been flanked by two cylindrical brick towers, in imitation of Domènech i Montaner, the one on the corner sculpted with the image of a luxuriant tree. Under the large square is the Petit Palau, a new multi-purpose hall with a capacity for 600 people.

Like La Pedrera, it is a supreme example of Catalan Modernisme, with its bold, brilliant and lavishly decorated architecture. The Palau is one of the most outstanding buildings in the city, and proudly bears the category of UNESCO World Heritage listing. But this was not always the case. The Palau was one of the last extravagances of Modernisme, and even in the 1920s it began to be questioned to such an extent that in the neighbourhood it was known as the “ironmonger’s palace”, and the architects of the time were in favour of demolishing it. Fortunately, they never achieved their aim and the Palau has become an institution with a special place in the collective memory of Barcelonans.

The Palau de la Música Catalana was opened in 1908 with a brief concert of works by Clavé and Händel. The façade of the Palau de la Música struck Barcelonans: of exposed brickwork combined with colourful ceramic mosaics, the corner features sculptures by Miquel Blay in the form of an enormous stone prow, representing an allegory of popular music with two boys and two old men embracing a nymph while Saint George protects them with the Catalan flag flapping in the wind, as it were. This is one of the most characteristic elements of the Palau, a work of great conceptual symbolism. The façade also has a mosaic representing “La balanguera”, a poem by Joan Alcover -today the anthem of Majorca island- surrounded by the singers of the Orfeó Català. Other points of interest on the exterior of the Palau are the peculiar ticket offices located inside the columns flanking the main door, now out of use. The rich details continue in the interior: a lavishly decorated foyer, with vaults lined with Valencian tiles and a double stair with golden glass balusters, are the hors d’oeuvres for the true jewel of the building.

The visually overwhelming concert hall is an inebriating succession of sculptures, stained glass, mosaics and decorative elements that constantly play with the perception of light and colour. The most characteristic image of the hall is its enormous and spectacular skylight of stained glass, which weighs a metric ton. This marvel of lavish art, in the form of an inverted bell, represents a circle of female angels forming a choir around the sun. Domènech i Montaner’s obsession with light is not limited to the skylight. He designed the concert hall, with its light steel structure, as a kind of glass box that filters the exterior light through windows that recall those of Gothic cathedrals and help to give the auditorium a sacred atmosphere. The stage of the concert hall is without doubt the most spectacular sculpture in the Palau. The proscenium features an unusual composition in pumice stone designed by Domènech i Montaner and sculpted by Dídac Massana and Pau Gargallo. On the left, the composition includes a bust of Josep Anselm Clavé and an allegory of the flowers of May, representing popular music. On the right, the bust of Beethoven personifies universal music. Above him, Wagnerian valkyries ride silently toward Clavé, symbolising the link between new music and the old Catalan musical folk culture. The stage is completed with a spectacular organ built in Germany and recently restored thanks to popular subscription. The hemicycle designed by Eusebi Arnau and faced with the ceramic fragment trencadís, features 18 sculptures that represent the spirits of music, together with a somewhat surprising Austrian coat of arms. A row of balconies and a colonnade of Egyptian influence make a modest contribution to the embellishment of a concert hall that is considered a sanctuary of music, in which musicians of the category of Rubinstein, Menuhin and Pau Casals have performed. Other elements of interest in the hall are the floral motifs that decorate all the ornamental elements, both on the ceiling and on the stained glass, and the mediaeval-like lamps, rather more suited to a castle than to a concert hall. Other spaces of interest in the Palau are the chamber music hall, in which one can still see the founding stone of the building, and the Lluís Millet Hall, which is perhaps the space that remains most faithful to the original design by Domènech i Montaner.

If you go round the Palau along Carrer Amadeu Vives and Carrer Ortigosa you will return to Via Laietana. In front of you stands the triangular building ![]() CAIXA DE PENSIONS I D’ESTALVIS DE BARCELONA (Via Laietana, 56-58), which for several years housed the Foundation of “la Caixa” savings bank and currently houses the Administrative Law Section of the High Court of Justice of Catalonia. This Neo-Medieval work (by Enric Sagnier, 1917) bears on its façade a sculpture by Manuel Fuxà conceived as an allegory of thrift, and a spectacular Gothic arch with stained glass windows. On the right is another building, also designed by Sagnier, known as

CAIXA DE PENSIONS I D’ESTALVIS DE BARCELONA (Via Laietana, 56-58), which for several years housed the Foundation of “la Caixa” savings bank and currently houses the Administrative Law Section of the High Court of Justice of Catalonia. This Neo-Medieval work (by Enric Sagnier, 1917) bears on its façade a sculpture by Manuel Fuxà conceived as an allegory of thrift, and a spectacular Gothic arch with stained glass windows. On the right is another building, also designed by Sagnier, known as ![]() EDIFICI ANNEX DE LA CAIXA DE PENSIONS (ANNEXE TO THE CAIXA DE PENSIONS, Jonqueres, 2). Here the architect used predominantly white stone decorated with a few Valencian tiles, but it has more modern lines and is one of the first examples of contemporary office buildings in the city.

EDIFICI ANNEX DE LA CAIXA DE PENSIONS (ANNEXE TO THE CAIXA DE PENSIONS, Jonqueres, 2). Here the architect used predominantly white stone decorated with a few Valencian tiles, but it has more modern lines and is one of the first examples of contemporary office buildings in the city.

At Via Laietana, turn right towards Plaça d’Urquinaona. From this square, the route continues to the left towards Plaça de Catalunya, the nerve centre of the city. Work started on the definitive design of this monumental circular square in 1925, after half a century of litigation between the City Council, the State and the private owners of these lands that for years marked the boundary between the old walled city and the new city that was spreading over the plain. The project was signed by Francesc de Paula Nebot, though he merely adapted an earlier design by Puig i Cadafalch, whom the military regime of general Primo de Rivera had condemned to ostracism. In fact, a work by Josep Puig i Cadafalch in the Modern Classicist style can be seen in the square on the corner of Rambla de Catalunya, ![]() CASA PICH I PON (PICH I PON HOUSE. Plaça de Catalunya, 9). Plaça de Catalunya marks the start of Passeig de Gràcia and the Eixample district, the true “motherland” of Barcelona’s Modernisme. In the middle of the square is the underground Tourist Information Office of Barcelona, the starting point for the Modernisme Walking Tours and one of the three Modernisme Centres of Barcelona. You can obtain the free discount vouchers for the Modernisme Route on presenting this guide at the Centre, which specialises in information on Modernisme. The adjacent shop sells products related to this artistic movement.

CASA PICH I PON (PICH I PON HOUSE. Plaça de Catalunya, 9). Plaça de Catalunya marks the start of Passeig de Gràcia and the Eixample district, the true “motherland” of Barcelona’s Modernisme. In the middle of the square is the underground Tourist Information Office of Barcelona, the starting point for the Modernisme Walking Tours and one of the three Modernisme Centres of Barcelona. You can obtain the free discount vouchers for the Modernisme Route on presenting this guide at the Centre, which specialises in information on Modernisme. The adjacent shop sells products related to this artistic movement.

Passeig de Gràcia is the backbone of the Eixample. It is a boulevard with a mixture of private residences, banks, cinemas, prestige establishments, coffee bars and many treasures of Modernisme. Initially, the boulevard was a simple dirt track that ran from the city walls of Barcelona to the neighbouring town of Gràcia. This began to change in 1827, when it was converted into a tree-lined boulevard. In 1852, the first gaslights were installed, and one year later a large leisure zone called Camps Elisis with gardens, bars, restaurants, dance halls, amusements and an open-air auditorium, was opened in the section between Carrer Aragó and Carrer Mallorca. In 1872 the first horse-drawn tramway began to operate, and from the 1890’s onward it became the new residential centre of the upper middle classes.

The fact that it is a wealthy area is shown in one of the most striking elements of the Passeig: its 31 benches-cum-streetlamps, designed in 1906 by Pere Falqués (55), which may pass unnoticed among the diversity of modern urban elements and the swarming traffic that invades Passeig de Gràcia every day. Other characteristic elements are the panots (pavement tiles), copied from the floor tiles designed by Gaudí for Casa Batlló, which were finally installed in the kitchens and service areas of La Pedrera. In 2002 the City Council repaved the avenue with them: hexagonal tiles that are all alike yet when set together reveal the marine motifs: an octopus, a conch and a starfish. The tiles were produced by the company Escofet and were among the first mass-produced paving tiles in Catalonia.

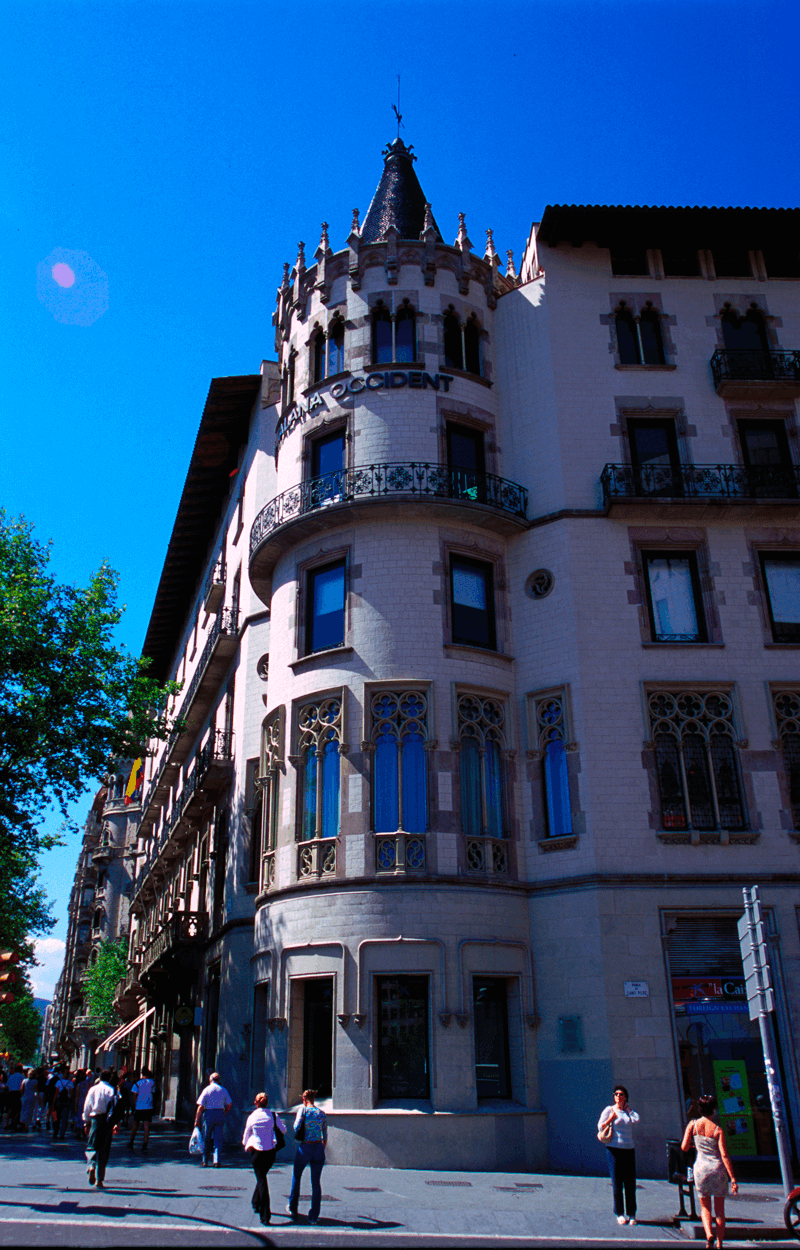

The architectural marvels of Passeig de Gràcia begin almost at the bottom of the boulevard with ![]() CASA PASCUAL I PONS (25) (PASCUAL I PONS HOUSE. Passeig de Gràcia, 2-4), at the closing of this edition, restoration work had begun the most Gothic work by Enric Sagnier i Villavecchia, one of the most prolific Modernista architects of Barcelona. The main interest of the building lies in the interior: it has stained glass windows representing medieval figures that can be seen from the exterior, a staircase with sculptural decorative elements and iron and glass lamps, and a majestic wooden fireplace. Built in 1890-1891, the Casa Pons i Pascual was originally two separate houses designed individually to make full use of their exceptional location, at the corner of Plaça de Catalunya and Passeig de Gràcia. A major remodelling of the houses was undertaken in 1984. The Route now continues up Passeig de Gràcia to Carrer Casp, where it is worth making a brief detour.

CASA PASCUAL I PONS (25) (PASCUAL I PONS HOUSE. Passeig de Gràcia, 2-4), at the closing of this edition, restoration work had begun the most Gothic work by Enric Sagnier i Villavecchia, one of the most prolific Modernista architects of Barcelona. The main interest of the building lies in the interior: it has stained glass windows representing medieval figures that can be seen from the exterior, a staircase with sculptural decorative elements and iron and glass lamps, and a majestic wooden fireplace. Built in 1890-1891, the Casa Pons i Pascual was originally two separate houses designed individually to make full use of their exceptional location, at the corner of Plaça de Catalunya and Passeig de Gràcia. A major remodelling of the houses was undertaken in 1984. The Route now continues up Passeig de Gràcia to Carrer Casp, where it is worth making a brief detour.

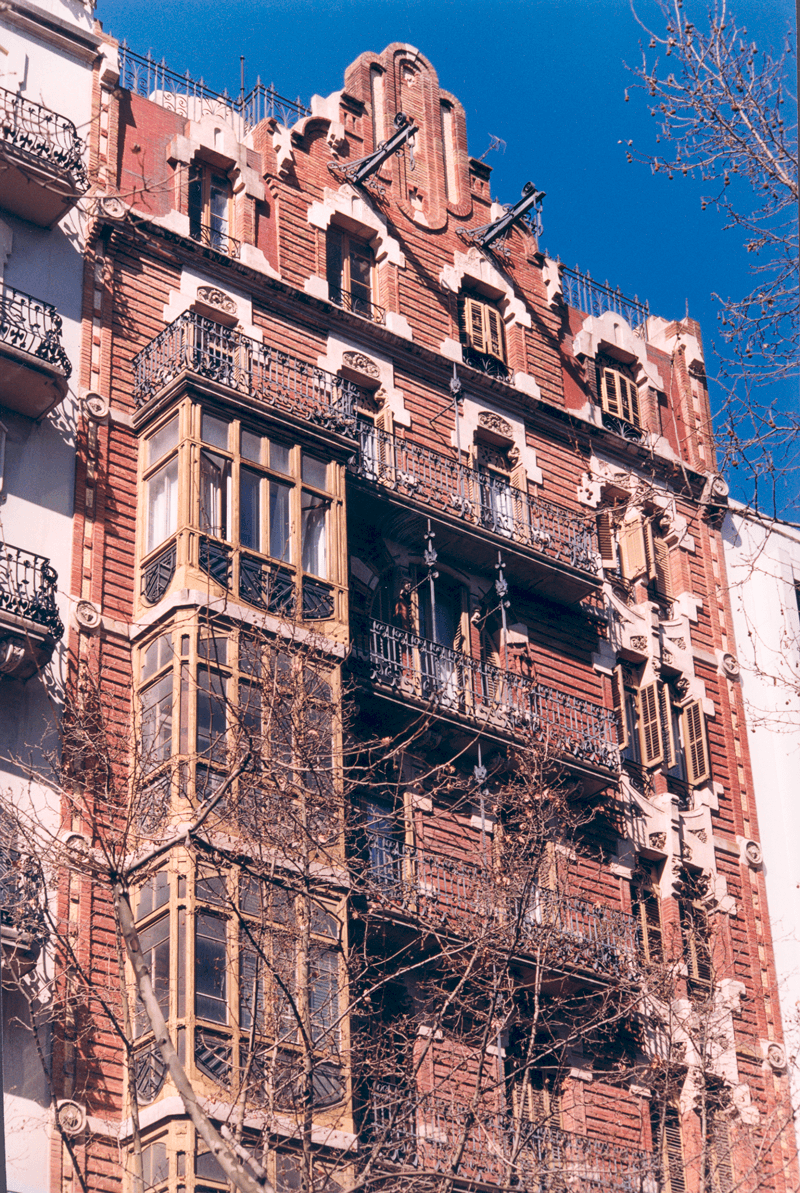

The first noteworthy building that you come to is the Modernista ![]() CASA LLORENÇ CAMPRUBÍ (26) (LLORENÇ CAMPRUBÍ HOUSE. Casp, 22) by Adolf Ruiz i Casamitjana (1901). With an exceptional bay window that occupies the piano nobile and the first floor of the building, Casa Camprubí is a good example of Ruiz’s work in the late nineteenth century, a period in which this architect made a very personal interpretation of a wide repertory of Neo-Gothic forms and elements. The following building on the detour along Carrer Casp is

CASA LLORENÇ CAMPRUBÍ (26) (LLORENÇ CAMPRUBÍ HOUSE. Casp, 22) by Adolf Ruiz i Casamitjana (1901). With an exceptional bay window that occupies the piano nobile and the first floor of the building, Casa Camprubí is a good example of Ruiz’s work in the late nineteenth century, a period in which this architect made a very personal interpretation of a wide repertory of Neo-Gothic forms and elements. The following building on the detour along Carrer Casp is ![]() CASA SALVADÓ (SALVADÓ HOUSE. Casp, 46), an Eclectic-style alternative by Juli Batllevell in a zone dominated by Modernisme. The adjoining building is

CASA SALVADÓ (SALVADÓ HOUSE. Casp, 46), an Eclectic-style alternative by Juli Batllevell in a zone dominated by Modernisme. The adjoining building is ![]() CASA CALVET (27) (CALVET HOUSE. Casp, 48) by Antoni Gaudí. Casa Calvet (1898-1899) was the first residential building by the brilliant architect in the Eixample, and with it he started a line that was followed by many houses that also used Baroque or Rococo elements such as the undulating forms, the peculiar treatment of the irregular surface of Montjuïc sandstone, the balconies and the bay windows. In Casa Calvet, Gaudí gave a different treatment to each element of the building. The façade features a Baroque bay window with wrought iron railings and reliefs representing different types of fungi in reference to the fact that Eduard Calvet, the first owner of the building, was an amateur mycologist. The decoration of the bay window includes the coat of arms of Catalonia and a representation of a cypress tree, symbol of hospitality. This is shown in the foyer and the ground floor premises, which have now been transformed into the Casa Calvet Restaurant (tables must be booked in advance: phone 934 124 012. For further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants). The restaurant has conserved the original furniture of Calvet’s office, from which he ran his textile emporium. Interesting features are the lamps, the benches in the reception room and the courtesy benches against the wall, the wood partitions that separated the offices from the textile store, the door handles and the beams of the ceiling.

CASA CALVET (27) (CALVET HOUSE. Casp, 48) by Antoni Gaudí. Casa Calvet (1898-1899) was the first residential building by the brilliant architect in the Eixample, and with it he started a line that was followed by many houses that also used Baroque or Rococo elements such as the undulating forms, the peculiar treatment of the irregular surface of Montjuïc sandstone, the balconies and the bay windows. In Casa Calvet, Gaudí gave a different treatment to each element of the building. The façade features a Baroque bay window with wrought iron railings and reliefs representing different types of fungi in reference to the fact that Eduard Calvet, the first owner of the building, was an amateur mycologist. The decoration of the bay window includes the coat of arms of Catalonia and a representation of a cypress tree, symbol of hospitality. This is shown in the foyer and the ground floor premises, which have now been transformed into the Casa Calvet Restaurant (tables must be booked in advance: phone 934 124 012. For further information see Let’s Go Out, the guide to Modernista bars and restaurants). The restaurant has conserved the original furniture of Calvet’s office, from which he ran his textile emporium. Interesting features are the lamps, the benches in the reception room and the courtesy benches against the wall, the wood partitions that separated the offices from the textile store, the door handles and the beams of the ceiling.

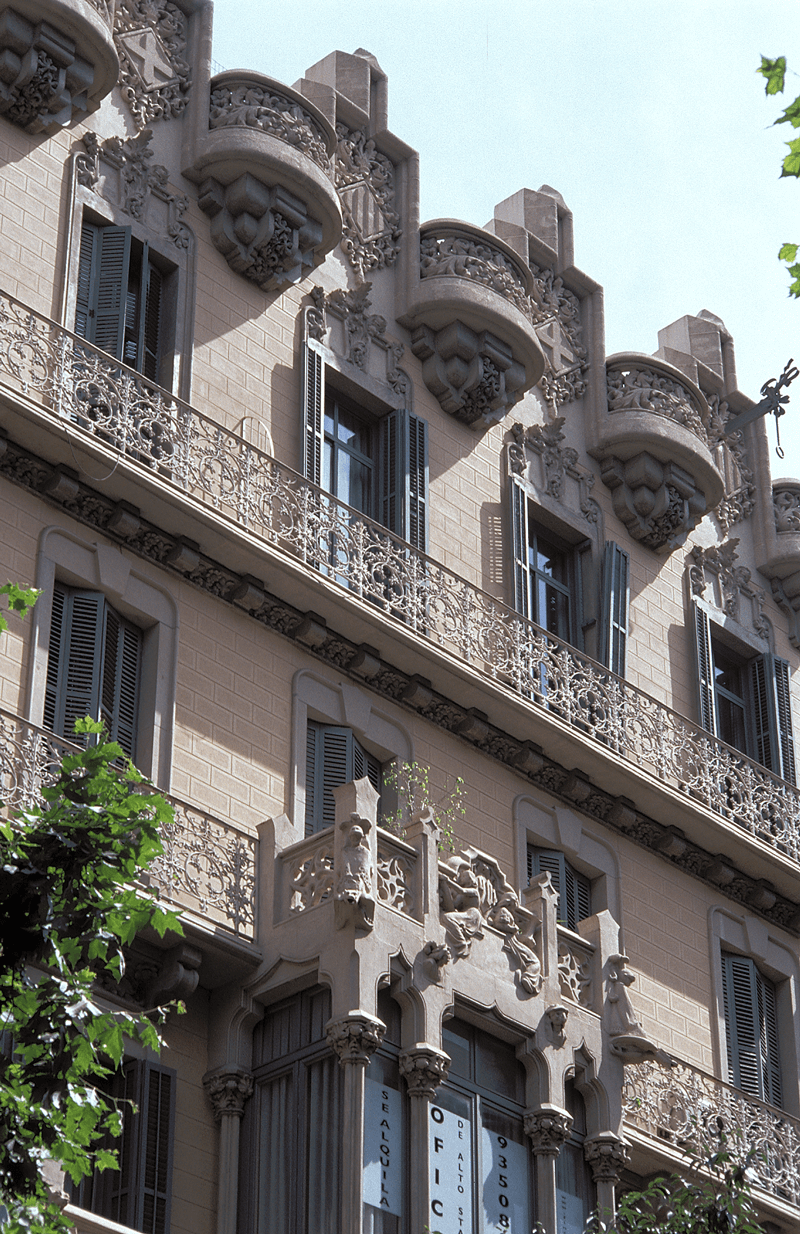

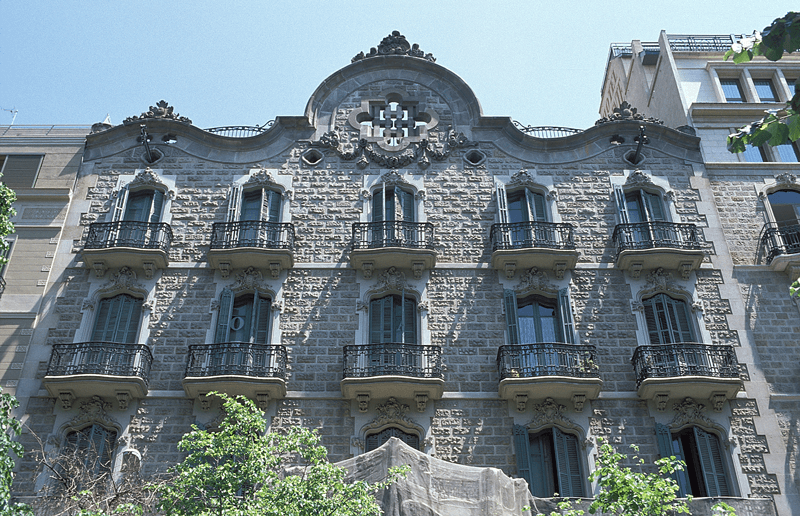

If you now retrace your steps along Carrer Casp to Passeig de Gràcia, you will come to the ![]() CASES ROCAMORA (28) buildings (ROCAMORA HOUSES. Passeig de Gràcia, 6-14).

CASES ROCAMORA (28) buildings (ROCAMORA HOUSES. Passeig de Gràcia, 6-14).

Like the Casa de les Punxes by Puig i Cadafalch (78), this is one of the largest architectural complexes in the Eixample. Though the blocks of this district were normally divided into individual buildings, this site was built as a single architectural volume to emphasise its magnificence. It is a 1914 building in a clearly Neo-Gothic style by the brothers Joaquim and Bonaventura Bassegoda, who paid special attention to the treatment of the stone on the façade and to the striking set of bay windows on the corner of Carrer Casp.

The route continues up Passeig de Gràcia to Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes, one of the three road arteries that Cerdà designed to communicate the whole grid plan of the Eixample (the other two are Avinguda Diagonal and Avinguda Meridiana). The crossing of these two large avenues is dominated by two striking buildings, though not Modernista in style. On the left is PALAU MARCET PALAU MARCET (MARCET PALACE. Passeig de Gràcia, 13), an urban mansion built in 1887 by Tiberi Sabater, which was transformed in 1934 into a theatre and has now been converted into a multi-screen cinema. On the right is the undulating Rationalist façade decorated with glass bricks of JOIERIA ROCA (Passeig de Gràcia, 18), a jeweller’s shop designed by Josep Lluís Sert in 1934.

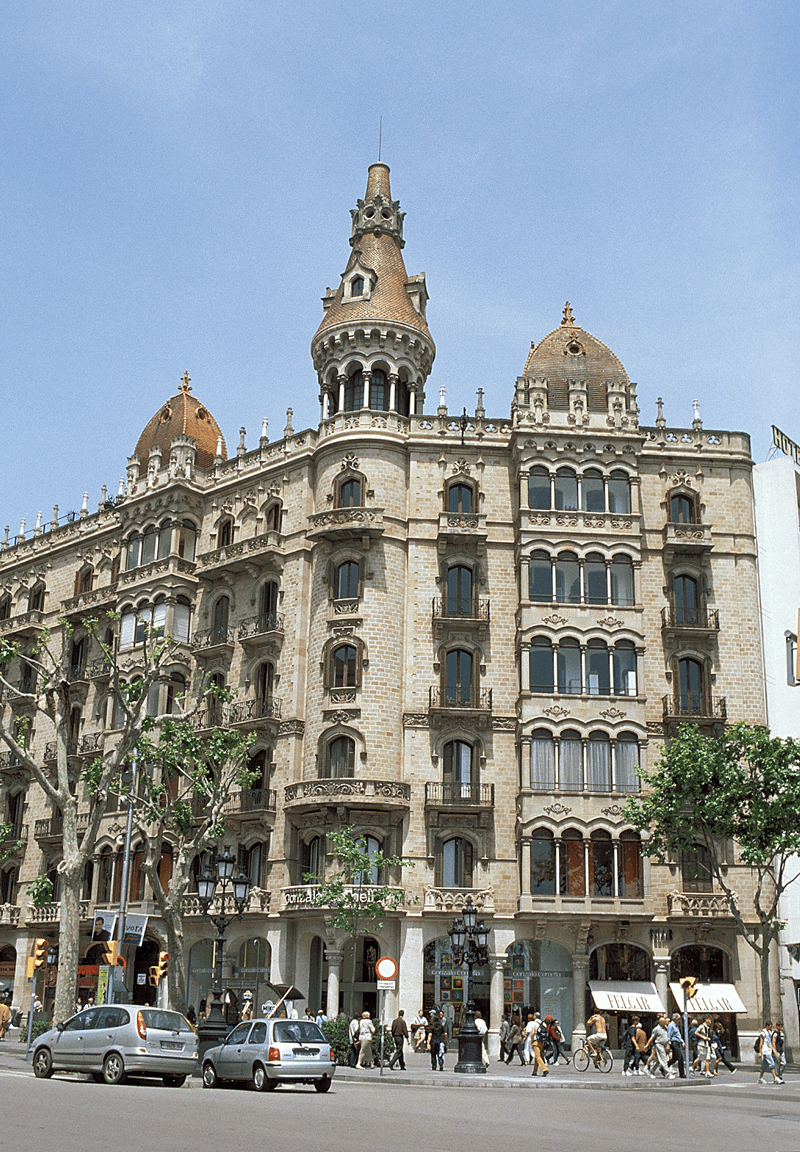

A detour to the left along Gran Via de les Corts Catalanes leads to several interesting Modernista buildings, but the first building is the Eclectic style ![]() CASA PIA BATLLÓ (PIA BATLLÓ HOUSE. Rambla de Catalunya, 17), a Neo-Gothic building by Josep Vilaseca (1896) that stands on the corner and is topped by two glazed ceramic towers crowned by wrought iron belvederes. After passing the monumental Cine Coliseum and the Neo-Classical building of the University of Barcelona (by Elies Rogent, 1896), on the opposite side of the avenue -on what Barcelonans call “the seaward side” of any street- you can see the