Barcelona Modernisme Route

Home /

Introduction to Modernisme

Modernisme: between Love and Hate

The art critic Francesc Fontbona is right in believing that Modernisme has gradually become “a kind of magic word within Catalan culture,” and that “there are those who, without wishing to, have given it a special charisma as a patriotic emblem that is totally excessive and out of all proportion”. This has not, however, always been the case, and one might be surprised to read articles of judicious people such as Carles Soldevila, Josep Plà and Manuel Brunet, for example, calling for the demolition of the Palau de la Música because they considered it to be an architectural aberration. This example is the tip of the iceberg of clearly anti-Modernista way of thinking that had a decisive influence on Catalan thought between the twenties and the fifties.

Amidst the love-hate relations that have been unleashed in the course of the time, Modernisme has a history that is not always easy to date.

The eighties

Alexandre Cirici Pellicer, a highly proficient historian and art critic, set the beginning of Modernisme in Catalonia in the period 1880-85, when five buildings as different as Casa Vicens, by Antoni Gaudí; the Víctor Balaguer museum-library in Vilanova i la Geltrú, by Jeroni Granell i Mundet the Academy of Sciences in the Rambla of Barcelona, by Josep Domènech i Estapà; the no longer existing Indústries d’Art de Francesc Vidal by Josep Vilaseca, and the Montaner i Simón publishing firm —today Fundació Tàpies—by Lluís Domènech i Montaner.

As the architect Oriol Bohigas states in a text in defence of Modernisme, this artistic movement “has such an extraordinary projection and intensity in Catalonia, and takes on at least such a sharp and transcendental personality as that of the foreign movements that were to some extent parallel, such as Liberty, Secession, Art Nouveau, Jugendstil or the Modern Style.

Modernisme sought modernity on the one hand and cultural regeneration on the other. A group of intellectuals whose core was the editorial staff of the weekly magazine L’Avens gave the movement content. They did not merely promote architecture, the cornerstone of Modernisme, but also the sculpture, painting, graphic arts, literature, theatre and the recovery of the traditional craft trades which were so skilfully used by the great architects.

The phenomenon came to an end between 1910 and 1914, according to Professor Joaquim Molas, in 1911 according to Oriol Bohigas, and between 1909 and 1910 according to the art historian Mireia Freixa. Whatever the case may be, it is clear that it was present in Catalan cultural life for about thirty years, though some late examples, such as the Casa Planells by Josep Maria Jujol (1923-24), are considered to be Modernista masterpieces.

Bruselas, Viena, Ålesund

When one travels to a city that also had its Art Nouveau period, it is easy to establish comparisons, though the styles are highly different. The Viennese Secession has a more distinct personality, but some houses of the Brussels Art Nouveau could be transported to the urban landscape of Barcelona. An interesting case is the port town of Alesund in Norway, which was destroyed by fire in the early 20th century. It was rebuilt in only three years, from 1904 to 1907, and this gave it a unique profile as an example of Jugendstil in the world. The period of this reconstruction coincides with that of maximum splendour of Catalan Modernisme, the first decade of the 20th century.

The promoters

The men and women who made Modernisme possible formed part of a privileged social group of manufacturers, investors, bankers and new nobility who had become rich in the late 19th century, according to Dolors Llopart; A factor that contributed to this was the repatriation of capital from Cuba after the loss of Spain’s last colonies.

For this upwardly mobile bourgeoisie, the clearest sign of distinction was to commission the construction of a new building in the Eixample, an expansion area of Barcelona that was being developed at that time. The admiration or envy caused by an unusual house, such as that of the Batlló family, redesigned by Antoni Gaudí, led Pere Milà to ask the same architect to build another one in Passeig de Gràcia, which became Casa Milà, known as La Pedrera. The institutions also wished to construct outstanding buildings in Modernista style, such as the Hospital de Sant Pau by Domènech i Montaner and the Sagrada Família by Gaudí.

Sculptors such as Josep Llimona, Miquel Blay and Enric Clarasó excelled in their Modernista statues. Desconsol by Llimona in the former Arms Yard of Parc de la Ciutadella, and La cançó popular, by Miquel Blay, on the corner of Palau de la Música’s façade, are two of the most representative sculptures of this phenomenon, but not the only ones. Montjuïc and Poblenou cemeteries, for instance, have a remarkable parade of Modernista sculptures.

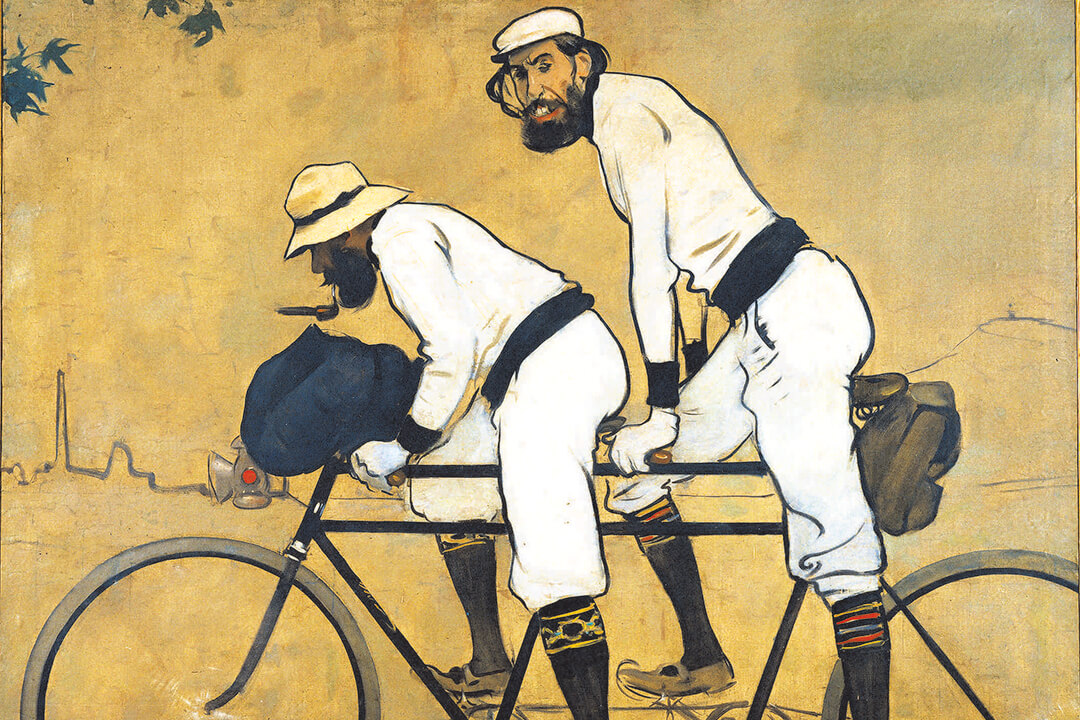

Painters such as Ramon Casas and Santiago Rusiñol were the main exponents of Modernisme in their art, and the cafe Els Quatre Gats, located on the ground floor of Casa Martí by Puig i Cadafalch, was a meeting point for those who placed their faith in the dictates of the new art form. Even some posters by Picasso can be considered to be Modernista, alongside the better known ones by Alexandre de Riquer and Adrià Gual.

In addition to the posters, there were the covers of some books printed by publishers such as Montaner i Simón, and periodicals such as Pèl & Ploma, Joventut, Hispania and Garba. In literature, Els sots ferèstecs, by Raimon Casellas, and Solitud, by Víctor Català, were two of the most important works of literary Modernisme. The performance in Sitges, in 1897, of La fada, a play by Jaume Massó i Torrents, director of the weekly magazine L’Avens, was a special moment in Symbolist theatre, which went hand in hand with Modernisme.

The Minor Arts

The concept of a minor art is certainly mistaken, but it has been used for so long that it allows us to understand each other. Joan Busquets is one of the major exponents of this excellent period of recovery of craftsmanship. He came from a dynasty of carpenters and created some of the most highly appreciated Modernista furniture of the time. He and the Majorcan Gaspar Homar were the most important figures in furniture.

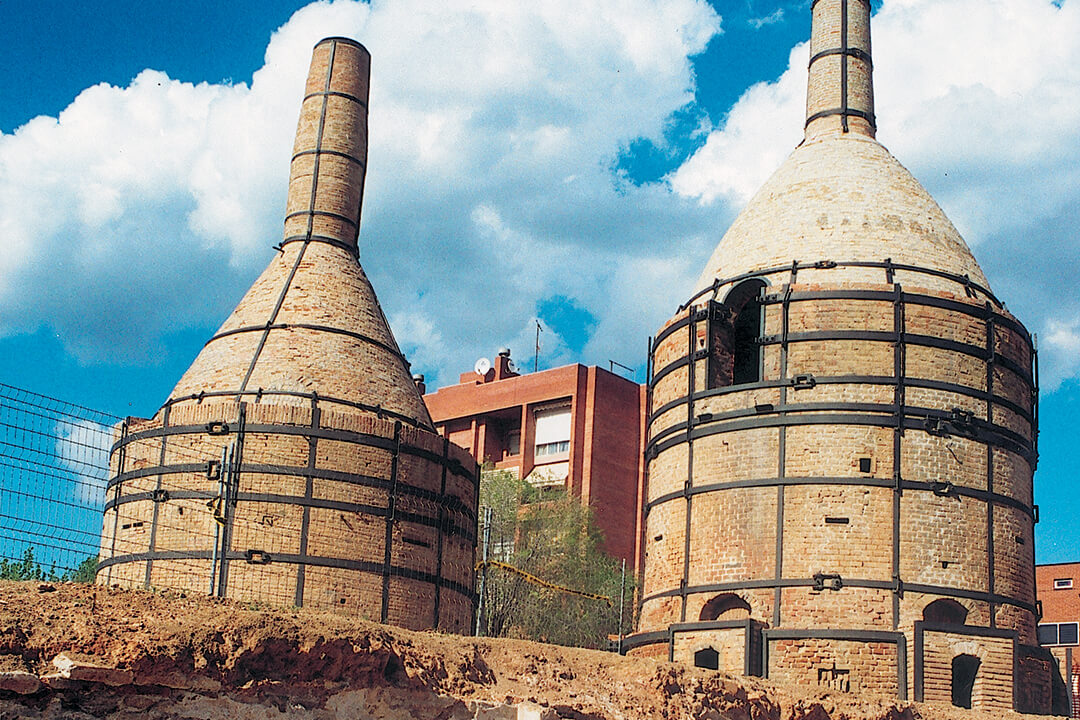

It would be difficult not to include in the values of Modernisme the famous stained glass work. A work such as the stained glass windows of the Casa Lleó Morera, by Antoni Rigalt’s workshop, is one of the best examples of the applied arts of the time. Other important works are the cast iron produced by the Manyach workshop, the ceramics of the Pujol i Bausis factory, the mosaics of the Escofet company, the jewellery of Lluís Masriera, and the terracotta work of Lambert Escaler.

The spread of Modernisme took place around the turn of the century, probably due to the impact of the Paris Exhibition of 1900, and also because at prosperous time in the economy, the Catalan bourgeoisie felt the need to give their dwellings personality. It was like a social triumph, and magazines such as Il·lustració Catalana published examples of the new houses of the bourgeoisie as positive new features of urban development.

Another aspect that is not always mentioned, but that was important in daily life, is the introduction of domestic improvements such as baths and washbasins, in addition to the use of tiles in kitchens and the spread of the use of laundry rooms. Not all have the beauty of the attic in Gaudí’s la Pedrera, but hygiene and comfort benefited from the advances proposed by many Modernista architects.

Decadence and defence

Noucentisme took a hard line with Modernisme, from which it took over. It considered the more extravagant examples of the former movement to be in poor taste, and many shops and establishments were transformed and decorated in a more austere, discreet and frankly boring style. We still have the photographs that show us what the Diorama Cinema and the Cafè Torino looked like, to mention but two of the many works that were forever lost.For years not even Gaudí was spared the general scorn, and time had to pass before he was again appreciated. Alexandre Cirici wrote in 1948: “When we ask the people who promoted it about Modernisme, except on rare occasions we are given the evasive answers of shame, a kind of repentance that wishes to bury the past. When we speak with members of the generation under the age of 30, however, we often find a great appreciation and interest in it.”

Few texts are more revealing of the post-war period, when Modernisme gradually began to be reconsidered. However, this did not prevent the demolition of Puig i Cadafalch’s beautiful Casa Trinxet in 1968, and struggle was necessary to prevent the same from happening to Casa Serra, also by Puig i Cadafalch, and Can Golferics, by Joan Rubió i Bellvé.

In 1968, with a major exhibition and the publication of Arquitectura modernista, by Oriol Bohigas and Leopold Pomès, the situation began to change and the interest noted by Cirici as a sign of the new generations paved the way for the recovery of a genuinely Catalan artistic movement. Modernisme had aroused love and hate that had to be overcome in order to contemplate it as it is, a great moment of artistic and ideological creation.

A Josep M. Huertas Claveria text

Get the Guidebook of Barcelona Modernisme Route

The Barcelona Modernisme Route is an itinerary through the Barcelona of Gaudí, Domènech i Montaner and Puig i Cadafalch, who, together with other architects, made Barcelona the great capital of Catalan Art Nouveau. With this route you can discover impressive palaces, amazing houses, the temple that is symbol of the city and an immense hospital, as well as more popular and everyday works such as pharmacies, shops, shops, lanterns or banks. Modernisme works that show that Art Nouveau took root in Barcelona and even today is still a living art, a lived art.

The Guidebook of Barcelona Modernisme Route can be acquired in our centers of Modernisme.